Key Messages:

- Studies on “non-specific back pain” are not helpful, just as studies on non-specific head pain would not be helpful, nor tolerated.

- A thorough assessment will identify the cause of pain in terms of offending motions, postures, and loads.

- Avoiding these pain triggers will allow a desensitization of the pain pathway.

- A specific and individualized diagnosis will guide each person on what to not do and what to do to rid themselves of pain and discomfort.

Most patients rarely receive the most important part of the prescription to get rid of back pain from their doctor—the knowledge and understanding of their condition required to become their own best advocate. They remain clueless and frustrated, left in the dark about what behaviors must be stopped in order to alleviate the cause of their pain. As well, they need guidance as to what is required to build a pain-free foundation that will allow them to get back to enjoying all their usual activities.

Getting “passive” treatments, such as prescriptions for pain medication without a plan to stop the cause itself, rarely creates a long-term solution. While medication may be a part of a broader approach, a thorough assessment of an individual’s specific pain triggers can identify the pain mechanism that will guide a targeted treatment plan.

Getting Past the Myths About Back Pain

There are several popular myths about back pain that can thwart recovery. “Non-specific back pain,” “ideopathic back pain,” and “lumbosacral strain” are terms used to label patients with back pain. But all that these non-specific diagnoses indicate is that the patient has not undergone a competent assessment of their pain mechanism.

Yet another popular diagnosis is “degenerative disc disease.” A “degenerative disc disease” diagnosis is the equivalent of telling your mother-in-law with wrinkles that she has “degenerative face disease.” I am so disheartened when a distraught patient expresses their fears to me regarding this supposedly progressive disease. When I tell them that in actuality they have no such disease, their reactions vary from relief to anger toward the person who mislabeled their condition.

It isn’t likely you will be able to hold your clinician accountable for these myths—that machine is too big. Nor should you hold onto the false hope that a typical fifteen-minute doctor’s appointment could provide you with a thorough enough assessment to create a complete road map to recovery.

Surprisingly, many people can actually be guided through a more thorough self-assessment that will reveal their precise pain triggers. This approach often introduces patients to the first accurate assessment of their unique causes of pain they’ve ever received. Based on the pain triggers identified, the next step becomes to guide movement strategies that allow motion while avoiding the triggers. In treating patients with back pain as individuals, they are able to understand why one approach may be very effective to remove pain for one patient but may hurt the other. Using the knowledge gained from their assessment they can:

- Remove the pain triggers.

- Create the foundation for pain-free movement.

The goal is to identify and follow an approach that is effective for them and their unique causes of discomfort.

The Assessment

Trying to diagnose painful back disorders based on anatomical structure alone is possible but difficult. But the only type of clinician who benefits from the tissue-based diagnosis (the type that comes from looking at X-rays, scans, and “poking around”) is the surgeon who is only looking to “cut the pain out.”

The evidence shows that the mechanism of back pain is almost always exacerbated by particular motions, postures, or loads—known as pain triggers. Motions, postures, or loads that exacerbate the back pain together with those that are tolerated can be identified through a series of simple diagnostic tests.

A complete rehabilitation plan is then designed to enhance function while avoiding these triggers. By following this system, back patients are categorized based on their intolerances. For example, workers with “spine flexion bending intolerance” will probably be exacerbated by sitting, tying shoes, etc., yet these same people find they possess very high load tolerance when the spine is not bent, but rather the motion is transferred to the hip joints.

The prevention plan and rehabilitation approach becomes clear. Assessment to properly classify back pain sufferers in terms of painful motions, postures, and loads provides clear clinical direction and eliminates the unhelpful non-diagnosis of “non-specific back pain.”

Essential Elements of Function – Guy Wires and Mobility

Certain loads on the spine are necessary and actually part of a maintaining a healthy back, but some are harmful and can, over time, accumulate damage. The healthy pain-free back is achieved with the optimal amount of load—not too much or too little—but each person is different in their reaction to loading. This is governed by biology, injury or training adaptation, genetics, and rate of repair.

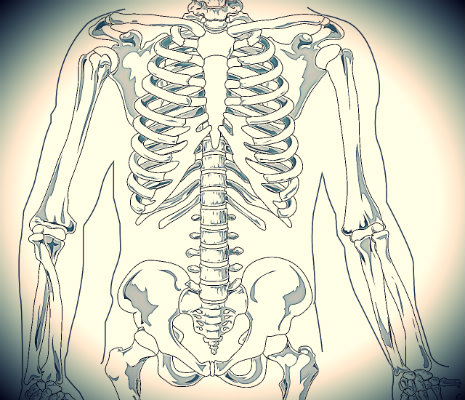

Proper muscle function is important to support a robust and pain-free back. Without the surrounding muscles, the spine would be rendered useless and incapable of supporting the weight of the upper body. Muscles are contracted in a coordinated manner that allow them to act similarly to guy wires, preventing the spine from buckling and giving way under high load levels. By stiffening and stabilizing the torso, these muscles allow movement to be propelled through the arms and legs.

This stress free movement is only possible when there is a stiffened core and corresponding mobility at the shoulders and hips. Just like a dump truck or a race car, some parts are stiffened and some create motion to enable the desired ability specific to the task at hand. People often wonder which should be valued more when it comes to using the core to manage the human spine: stiffness or mobility. It turns out both are needed. Your spine muscles are constantly tuning this stability/mobility interplay, and this “sweet spot” is governed by a set of movement principles.

This stress free movement is only possible when there is a stiffened core and corresponding mobility at the shoulders and hips. Just like a dump truck or a race car, some parts are stiffened and some create motion to enable the desired ability specific to the task at hand. People often wonder which should be valued more when it comes to using the core to manage the human spine: stiffness or mobility. It turns out both are needed. Your spine muscles are constantly tuning this stability/mobility interplay, and this “sweet spot” is governed by a set of movement principles.

What Causes Back Disorders?

While there are many causes of back disorders, the scientific literature evidence is strongest for several possible mechanical causes. Once the patient has experienced pain, and the nerve system is sensitized, how the person reacts to the pain is modulated by a host of variables that can increase or decrease the pain sensitivity.

Biology, adaptation, size, and previous injury history all influence the reaction to load magnitude, repetition, and duration. For example, the spinal discs have a fatigue life—in other words, a limited number of bends they can withstand before they become painful. The possibility for ease of motion between discs is modulated by variables such as hydration (time of day), the corresponding load at the time of the bending motion, the direction of the bending axis, and a patient’s routine and approach to training, among other factors.

If, for example, an individual continues to bend a painful disc, by continuing to flexion-stretch their back, they will most likely experience worse symptoms—or at least a recurrent aggravated situation. The same mechanism is exacerbated by extended periods of sitting—here the spine (particularly the lowest lumbar discs) is flexion bent.

Strangely, these flexion-intolerant patients are sometimes told to pull their knees to their chest to obtain relief. This motion activates the stretch receptors in the back extensor muscles, resulting in painlessness for about fifteen minutes. But unbeknownst to the patient, this bending has caused further damage and/or sensitization of the underlying pain mechanism. While the patient may have found a “quick fix” or short-term cure, they are actually sensitizing their pain trigger and inviting additional pain attacks in the future. These types of stretches initiate a dangerous cycle, temporarily numbing pain while inciting continued long-term pain.

While these types of patients often find relief through frequent posture change, and even fast walking, they simply cannot tolerate sitting. Sitting posture can be assisted with lumbar support in the form of a small cushion to prevent the lumbar flexion trigger. Special exercises designed to combat the cumulative stresses from sitting are also usually helpful. Here, encoding the “hip hinge” movement pattern to replace the spine bending pattern is important.

This is just one example in which provocative testing and classification of the back pain sufferer results in better prevention and rehabilitation approaches than a classic rushed doctor’s appointment. There are many other sub-categories in which the specific strategies to avoid the cause and create a pain-free foundation will differ. By following a few rules for back health and function, a plan to build resilience to pain triggers is possible.

Consider the specific movements used by athletes, construction workers, and farmers. With an appropriately identified set of specific stressors, all of these individuals are able to modify these movements in order to eliminate the pain triggers and go about their required work in a more spine-sparing fashion. Like any other type of pain, the more the triggers themselves are avoided, the faster the sufferer will be able to desensitize their reaction to them altogether.

Assessment and Provocative Testing: Motions, Postures and Loads

The typical orthopedic exam determines the range of spine motion, as well as some neurological measures such as strength of reflexes, and perhaps some qualitative measures of muscle strength. These measures provide little guidance for designing prevention and rehabilitation programs. As an example of this, we published a study in which we tracked the progress of back pain patients who sought treatment in a pain clinic (Parks et al, 2003). What we found is that the scores obtained from the initial assessment had very little correlation with which patients actually experienced a full recovery and returned to work.

Asymmetries of both strength and movement (particularly in the hips) have been shown to be associated with, and predictive of, back disorders. Imbalance in torso muscle endurance around the torso has also been shown to be predictive of future back disorders. Thus, correction of these asymmetries with corrective and therapeutic exercise should be the first stage of any rehabilitation program.

Provocative testing—in other words, tests to intentionally provoke discomfort—is another essential element in determining which postures, motions, and loads are exacerbating of the pain and which ones are well tolerated. One such example involves having a pained patient sit upright on a stool and pull upright on the stool seat pan to compress the spine. Usually this shouldn’t cause any discomfort. Next, the patient would slouch, causing flexion through the spine, and repeat the pull. Should this cause pain, then we have identified a flexion-intolerant patient. Activities that involve a forward slump utilizing poor posture can now be identified as pain triggers.

I provide many examples of pain triggers such as extension intolerance or perhaps intolerance to specific muscle activation strategies in Back Mechanic. Avoidance of the pain trigger together with specific exercises can rebuild resilience and stamina for pain-free activities.

What Every Patient Needs to Know

The occupational medical system does not always provide all involved parties with the necessary information to optimize pain-free movement and restoration of occupational work. Every back pained worker needs to know the following to facilitate recovery:

- Exam results—Current scores will give context to the future goals

- Natural history and prognosis—There is no evidence most back disorders last into retirement and they are, in fact, often addressed with appropriate classification and treatment plans

- Causes of pain—Patients are often amazed to find out the way they move and activate muscles can eliminate pain

- What they must avoid—Removing the cause of the disorders is obvious, this also allows the therapy to be more effective via two mechanisms:

- Pain sensitivity is reduced by winding down central sensitization

- Allowing the tissue to heal/adapt

- Their recovery plan—Which should look like the following progression:

- Beginning by addressing the movement disorders with corrective and therapeutic exercise

- Stabilizing those body areas needing stabilization and mobilizing those which need mobilization

- Enhancing endurance so joint sparing movement patterns can be repeated even when fatigued

- Building some strength and possibly some power generating ability at the hips and shoulders if the occupational demand is present (McGill, 2016).

Implications of the Tests

Provocative testing, when combined with movement screens for joint symmetry of motion, strength, and endurance, underpins a powerful classification for back-pained individuals. Classification enhances the therapy plan and identifies which patterns must be avoided. The testing process is continued throughout the recovery process to define tolerable levels of load in specific postures and movements so that the “dosage” of therapeutic exercise can be tuned to the individual.

In Summary

There is no such thing as “non-specific back pain” or degenerative disc disease—there are only those individuals who have not had a thorough assessment. There is a mechanism that can be identified as the direct cause of the vast majority of back pain. But the traditional medical system approach based on fifteen-minute appointments provides no opportunity to show the patient the cause of their pain nor an appropriate guiding plan of effective ways to get rid of the cause and build pain-free movement.

The book “Back Mechanic” is a step-by-step guide to empower the reader to become their own best advocate to get rid of their pain. Rich illustrations guide the process. There is no such thing as a “one size fits all” approach that will work for all individuals. This book is about learning your unique triggers and how to avoid them, as well as a comprehensive guide to each set of corrective exercises that will adjust your movement patterns and rebuild your tolerance and strength.

The book “Back Mechanic” is a step-by-step guide to empower the reader to become their own best advocate to get rid of their pain. Rich illustrations guide the process. There is no such thing as a “one size fits all” approach that will work for all individuals. This book is about learning your unique triggers and how to avoid them, as well as a comprehensive guide to each set of corrective exercises that will adjust your movement patterns and rebuild your tolerance and strength.

I am happy to say the methods illustrated within this guide enable 95% of people who have been told they should consider surgery to avoid it. This guide is key for any individual looking to take control of their painful spine, and become their own health advocate. We are all capable of becoming our own Back Mechanic.

“Back Mechanic” is available from: BackFitPro.com and Amazon.

As a physio, I am sorry to say that the insight “an individual continues to bend a painful disc, by continuing to flexion-stretch their back, they will most likely experience worse symptoms—or at least a recurrent aggravated situation”, generated huge catastrophe in public and clinician. they overextend their back with co-contracted back extensor and abdominal muscles, with the fear of damaging their disc, which on the other hand causes compressive force further sensitising the underlying tissue. that’s why they get relief from flexion stretch.

Dr McGill’s biomechanics oriented approach has been proved ineffective for people suffering from disabling back pain which is driven by multidimensional. Highly recommend look up Profession Peter O’Sullivan.

Pain is multidimensional, biomechanics is only part, maybe small part of the whole picture, overemphasise the biomechanical impact on the human body, missing bigger contributor to their pain, is disastrous for lots of people.

Just finished reading this, excellent bought it for my wife who is a long time sufferer.

My wife has had two back surgeries in the last five years, both for spinal stenosis which caused crippling sciatica and prevented her from being active. She has been very active her whole life, an avid hiker and gardener and project person, not averse to picking up 50 lb bags of compost or sand or whatever. She went from doctor to doctor for awhile, one surgeon went straight to recommending fusing several vertebrate from looking at the MRI, no physical examination. She ended up choosing a neurosurgeon who was a spine specialist who was highly recommended and told her the details of her condition. He was conservative in his approach, the first surgery was a big improvement but there was still significant pain and they went ahead with the second surgery. Almost three years of relief. She was back to 30+ miles week of hiking and walking plus her gardening and projects. Lately the sciatica has returned. Her walks got shorter and shorter, now less than 2 miles/day, sometimes with 2-3 days off. In the past I’ve bought perhaps 6-7 back books, she didn’t show much interest in any of them after a cursory examination. This week “Back Mechanic” arrived. I set it on the coffee table thinking I’ll read it when I get the time. Today she tells me “I’m highlighting some places in that back book, hope you don’t mind”. The she proceeds to talk for ten minutes about different things she’s read in the book, about spinal stenosis, traction, various exercises to do and not do, why some yoga and pilates is not recommended, etc, etc. Great, great book, just what we needed. In a couple of weeks a new visit to the neurosurgeon, I think she’ll be well armed both to ask questions and understand the answers and make a decision about the next step. Very great book, thank you very much Dr. McGill.

Wow, Mike, that is so great.

How is this book for someone with no back problems?

Because it does seem like an interesting read

Please make kindle version of your new book available

Hi!

Is there an e-book version? I live in Spain and the shipping cost is huge, plus I’d like to get started with the book instead of waiting for it to arrive.

Thank you!

Forget what I said, I just had to order the book from the european web.

Movement is like a magnifying glass to the body. When your client moves watch them like a hawk. Start from the ground up and address any patterns that don’t look right. This may mean dropping that pattern altogether or working on it every session until corrected.

Can someone summarize the practical course of action a patient of back pain may take in simple terms? Who examines the patient to determine the body areas needing stabilization and mobilizing those which need mobilization for example? Is it the patient himself, if not who? Certainly not the conventional doctors. Thank you.

Abdul, I hope Dr. McGill will reply but I will also offer an answer.

I am an example of someone for whom surgery was recommended, and who avoided it and returned not only to previous function but to new levels of strength and age/weight group records in powerlifting. I did this by doing exactly what Dr. McGill advocates. He says above, “Surprisingly, many people can actually be guided through a more thorough self-assessment that will reveal their precise pain triggers.” I recommend you re-read the description next to the picture of his book above, and order the book – I will be ordering my copy as soon as I finish typing this message.

Each of us who suffers from back pain must become his own best advocate, and each of us must learn what helps us and what hurts us. You will always find me with a sweater wrapped around my waist when I am sitting because a lumbar support when seated is important for me. You will find me deadlifting a heavy barbell because strength, too, is important for me, and you will find me able to do splits because that kind of hip mobility and hip and hamstring flexibility is also important for me.

-S-

Thanks Steve. I am ordering the book. I understand, the onus is on *you* empowered.

I used Ashtanga yoga to become pain free. It has become part of my life and with a combo of KB training and yoga I have strength and mobility. Perfect combination.

Super summary. As an LMP, I’d also like to add that there is a huge educational challenge when new clients come in with undiagnosed back pain and want their lower backs worked on. Similar to the knees-to-chest stretch, sure, doing a lot of work on the lower back might reduce pain…for the moment. It’s probably going just exacerbate things over time. Hips, shoulders, the entire abdomen, shoulders…these are the things that likely need manual attention to assist bringing things into balance. And then all the appropriate exercise. If your back is sore, please don’t ask a manual therapist to be adding significant pressure to your unhappy lower back.

Amazingly well written article. Goes to show how swings are so important in developing a strong back.