“Give them great meals of beef and iron and steel,” wrote Shakespeare in Henry V. “They will eat like wolves and fight like devils.”

Given a choice, I do not think these fierce warriors would have gone to a fast food joint to get their beef. It has been established that the average McDonald’s customer finishes his meal in a little over ten minutes. I wonder if there is an inverse relationship between the quality and the time it takes to consume it? I know that in strength training there is — a kid who rushes from set to set will never get strong.

As a reaction to the fast food trend, Italian food writer Carlo Petrini launched a “slow food” movement to promote leisurely meals to enjoy the company of one’s friends and family and even to taste the food. Perhaps we should do the same in strength and even conditioning?

The 3 Types of Rest Intervals According to Russian Science

Russian sports scientists identified three types of rest intervals within a session (Matveev, 1991):

- Ordinary interval. It provides “relative normalization of the function.” By its end the work capacity approaches the level before the previous exercise bout, to the point where neither the quality nor the quantity suffer.

- Stress interval. “Its duration is so short that the next load [set] is overlaid onto the remaining functional activity of certain systems of the organism caused by the previous load [set]. As a result, the effect of the next load [set] is increased.” This interval is shorter than the ordinary one, obviously. Performance does not have to go down but it comes from a greater effort.

- Stimulation interval is the shortest interval after which the performance increases. Note that this is increase is short term rather than long term (facilitation rather than supercompensation). As fatigue sets in, facilitation stops taking place.

Note that the same given time interval may change with fatigue — from stimulation to ordinary to stress.

In elite weightlifting and powerlifting stress rest intervals are very rare. The only high profile example I can think of is Louie Simmons’ “dynamic effort day.”

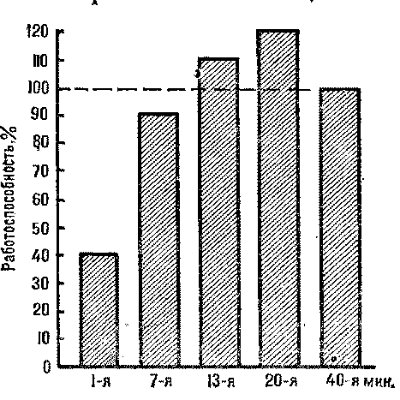

A stimulation interval is most common among American powerlifters, especially those following the classic 1980s methodology of Coan & Co. They would think nothing of taking twenty minutes between heavy sets of squats and Soviet research supports this practice in this context. Hippenreiter (quoted in Zimkin, 1975) had his subjects do an all-out set of military presses. Their ability to repeat their performance was still down by 10% on the seventh minute. By twelfth minute the work capacity exceeded the initial value and stayed up until the 25th minute.

It must be stressed that the above timing applies all-out sets; recovery is much quicker in sets stopped far from failure, as is the case in Olympic weightlifting. Ordinary intervals are standard in that sport. “Multiyear research has demonstrated that rest intervals usually range from 2 to 5 minutes. The next set should be performed when the athlete is subjectively ready for it.” (Medvedev, 1969) Other authorities like Vorobyev (1981) were in total agreement.

A number of Russian powerlifters, including the national team, follow a training methodology derived from the Soviet weightlifting one. As expected, they practice ordinary rest periods (although they appear to be stress intervals to Westerners). Consider these recommendations by Sheyko (2008):

80% 1RM x 5 reps/2 sets—2-3min

75% 1RM x 5/5—4-5min

90-95% 1RM x 1-2—5-7min

Any experienced American powerlifter will tell you that the first is nearly impossible and the second is brutal. Not so to Russians, due to their high work capacity developed by their training methodology (a topic for another conversation). For them these are ordinary intervals.

Rest Completely to Achieve Your Potential

In summary, if you are only practicing incomplete recovery between your sets of strength exercises, you will never achieve your potential. Density protocols certainly have their place in hypertrophy training — but they are an equivalent of fast food, to be consumed only occasionally. Most of the time your rest periods should be ordinary (you feel recovered) or stimulating (much longer than whatever your “feelings” are telling you). An example of the former is ladders; of the latter grease-the-groove.

Next time we will talk about the benefits of longer rest periods for “conditioning.” Until then, practice “slow rest” and enjoy your strength gains!

Pavel, I don’t fully understand the need to rest that long if sets are far from failure. Personally, I can take a big lift, like squat or deadlift and do singles or doubles EMOM with varying weight every set from 65-85% for quite some time. I can routinely do 50+ such squats with no fatigue and no recovery issue. I can often repeat my performance the next day. And I am a strong squatter, my atg high bar squat is over 3xBW. However, if I do sets of 5 at similar percentage I get floored even with 10+min rest intervals. I can barely do more than 4 sets even with varying weights and after such workout I’m out for days. What does that mean, should I avoid 3+ rep sets because my body is just that way or does that tell me something I don’t know?

Hello

Excellent article. Reading a recent article about the training of Kazakhstan

lifters the rest periods BETWEEN EXERCISES was 15-20 min. From what i understand

the stronger one becomes the more stress a given percentage of 1rm is to him/her.

In other words when you are just starting out one can repeat his 1rm (bench press) in 48 hrs. or less.

When one gets near his genetic potential one cannot repeat his 1rm for about 10 days to 2 weeks.

Pavel, Great article! I have been following your work for quite some time.

Just a quick story to drive home your point:

I was going through a high volume bench phase for a while and decided I wanted to do 10 x 10. Not the GVT style with short rest but my way with as much time as I needed. I started at 225. Over the weeks I ended up getting to 265 lbs for 9 sets of 10 and 9 reps on my last set. Just about always took me 75 minutes. I LOVE this style of training.

Walt, see an SFMA doc.

Pavel,

One of the reasons for having success with your Plans (ROP, Experimental, 5x5x5, ES etc…) is I REALLY TAKE MY TIME. Often surpasssing the the 5 min. rest periods. I very rarely miss a rep and almost never train to failure. After reading PTTP many years ago, this principle has stuck with me ever since.

Looking forward to your future articles and attending PLan Strong Italy. Thank you!

Thanks, Louka!

Pavel,

Thank you for the article. It looks like for the simple goal (100 swings inside 5 minutes) the rest periods is forcibly compressed for everyone, Right? What is the reason for it?

I have been training S&S last few weeks. Currently I am at a point where I am able to swing 8×10 using a 24kg, however it takes about 12-13 mins, since I have to to take longer rest periods (usually 1.5-2 minutes). As soon as I compress my rest period (e.g. 30 seconds) I am out of breath. What is the best approach / course of action for me to reach the simple goal sooner but safely ?

My TGUs with 16kg, I am able to complete within 10 mins.

Abdul-Rasheed, do not compress the rest periods but work up to 10×10 first.

Al Ciampa insightfully pointed out that S&S swing plan is alactic+aerobic in training; then glycolytic in testing and the build-up to it. So do not compress the rest periods until it is almost easy.

Thank you !

Pavel,

So, one should work up to 10×10 in swings before moving up to the next size bell? (I must have missed that in the book) So, I should have done that first with the 32kg before playing with the bulldog? Funny, I read the book 3 times and still don’t recall seeing that. In any case, there must be an entirely different protocol for the getup? 10 hard reps is quite enough. My problem is after a 2 reps per side, my shoulder gets shaky, so it’s dangerous. (Which is why I need the long rest). The sit-up part is easy for me. Should I start adding supplemental presses?

Walt, absolutely. The lower number of sets is only present when you are starting the plan.

It is OK to rest longer between your get-ups but have your shoulder checked.

Thanks, Pavel. This makes it more interesting than just a set # of 5. I’ll go back to the 32kg until I can comfortably do 10×10. I already know my shoulders are trashed- many separations from high speed crashes on skis and dirt bikes. I’ll just work through it. Sorry to bother you again: but on getup a: what else can I do to assist shoulder stability? Presses? I can do around 5 with the 32kg (strict) and can press the bulldog once on a good day. Some say handstand stuff is good. Should I try to add something like that in my program?

Since this is the second time in these comments I’ve read this, I’ll try to explain…

S&S swings is alactic work+aerobic recovery “IF” you do not crunch the rest intervals, whether driven by ego or, “it feels easy today”. For the plan to work, you have to stimulate the body for the adaptation you seek.

That you can do more work in less time (condensed S&S swings), on any given day, does not mean you are stimulating the proper cellular adaptations, and so, you will hit a wall in your training, re: not make it to the next bell size, or not achieve 100 x swings in 5 min with your current bell.

The “thing” that you should be trying to stimulate with this protocol is doing more work under aerobic-dominant fueling. This takes patience and discipline. Rest longer, be patient, do the work, and over a short period of time, you will increase your work output while still being aerobic. Then, you can “test” while fueled predominantly by glycolysis. Whatever your test outcome, go back to training under aerobic fueling.

Just because glycolysis is always there to kick in, like a turbo charger, and increase your output, does not mean that this is also the goal of your training. So, rest longer… do not forcefully reduce your rest periods… let your body adapt and your rest periods will natrually decrease… I’m certain that I read this some place before…. ;]

There is some anecdotal evidence that if you train properly and patiently, you can achieve 100 x swings in 5 min while being aerobic. So, train to a HR, or lactate threshold, or rest longer during your swings—whatever you like to call it–but training is different from competing.

Well put, Al!

Al, I have read this post a few times. I came back to it after a few weeks and read it again. The terminology alactic, glycolytic, aerobic etc. was throwing me off. I think I ‘get it’ now, somewhat, after reading about these energy systems elsewhere. I will eventually undertstand it fully. Meanwhile I will do my S&S as you say. Thank you.

still waiting for your new books pavel sir

Noe, have you reached the “simple” goal in S&S?

“Any experienced American powerlifter will tell you that the first is nearly impossible and the second is brutal. Not so to Russians, due to their high work capacity developed by their training methodology (a topic for another conversation**)”

**I am very much looking forward to that conversation. Is this a topic you plan to cover soon?

Yes, Zach. “Work capacity” has joined the fashionable jargon of the industry—yet very few know what it means. Two blogs on the topic are on the way this spring.

Excellent news, glad to hear it.

I’ve always used work capacity to describe, “how much work you can do in how much time”. Like moving a pile of heavy rocks from one side of the field to the other, or, shoveling winter snow ;]

Higher strength level and higher conditioning level combine and lead to increases in this ability. So, since we do not have a common understanding of what conditioning is, I can see how work capacity is also a muddy term.

Looking forward to these blog topics.

Pavel, I am really looking forward to this! I’ve always felt that “work capacity” to one guy might mean something totally different than it does to another guy. In terms of ability to continue doing “X” event/feat/exercise/function for whatever time limit or distance.

One extreme is a guy I used to work with that used a farmer’s walk with a 175lb block of steel as his “work capacity” test for anyone that wanted to train with him. Nothing else mattered to him. Nothing. If you couldn’t carry that block whatever distance he deemed “appropriate” – he wouldn’t even help the guy out. I carried it almost twice the distance he was able to – without training on it. At that time it was 25lbs over my bodyweight. I wasn’t trying to get him to “help” me with my training, but I did want to take the test to see what all the buzz was about.

He actually declined training with a guy that was a 700lb deadlifter (at 242lbs bodyweight) because the guy couldn’t carry the 175lb steel block whatever completely random number of feet the former coworker deemed “necessary.” The 700lb deadlifter said that unless 175lb steel block man could deadlift 400lbs for 10 consecutive reps, he (the 700lb deadlifter) wouldn’t even consider the 175lb steel block man eligible to begin training with him. Because his “work capacity” wasn’t high enough yet. Nevermind the steel block guy wasn’t capable of deadlifting 400lbs even once. Because his back wouldn’t allow him to lift anything over 300lbs without issues.

So “work capacity” has interested me for a long time.

Didn’t mean to say “farmer’s walk” – meant to say just a plain bearhug and carry.

Very amusing, Ben! Good points.

Walt, in S&S the compressed rest periods apply mostly to testing and the sessions leading up to it, so take your time.

I take it this only applies to barbell training? Having completing the Simple and Sinister program minimum a while ago and now working with the bulldog, I find I have to increase my rest intervals no matter what, even though I am not winded at all. I don’t have a barbell. (no space) So, I only do kettle bells, sandbags, and BW. Any way, in s&s kettlebell training, you have to do all the swings in 5 minutes and get ups in 10. I can do it all with an 88 pounder, if I rest long enough. But , am I really getting getting anything out of it if I take, for example, twice the required time? Before, when I was using lighter bells, I set a timer and always tried to do it in the prescribed time.