“The grass is always greener on the other side of the fence.

Usually because the manure is deeper.”

—Gene Dudgeon

PART 1: TALL PEOPLE PROBLEMS

Full disclosure — I’m 6’ 6” tall, barefoot. I hate ceiling fans, airplanes, and little cars. I can’t buy clothes off the rack. Twice a year — when the time changes — I spend an entire day changing clocks hung on the walls at work (job security). And NO, the air up here isn’t better than the air down below. I have always had to work extra hard on my pressing and deadlifting. Pistols are my nemesis — I am convinced they are only around to ruin me.

At my SFL Certification in 2013, Pavel commented “That is one long press” (referring to a military press that took me half a day to complete). I totally agree. (I have hit rafters, drywall, and light fixtures during some pressing workouts — I don’t even attempt to snatch in rooms with a ceiling less than nine feet.) Finally, Someone appreciates the plight of the tall people in this world. Considering that 95% of the world’s population is under 6’3”, I optimistically consider myself in an “elite” category. When it comes to grabbing defensive rebounds, changing the clocks, and seeing over crowds, being tall is a huge advantage. From a strength standpoint, being tall is a HUGE obstacle.

PART 2: LEVERS

At the NATA (National Athletic Trainers Association) Annual Symposium I attended last year, one presenter reported a study on the deadlift. They were looking at the stresses on lumbar tissue. Their suggestion: if you are over 6’, deadlifting isn’t a good idea (based on the lever arms, forces, and angles). Do I agree with this 100%? Absolutely not. Do I think height needs to be a consideration in training? Absolutely — training taller athletes does need some consideration.

But everything is relative — your body is your body and you should be able to do whatever you want to do, right? I agree with to some degree regarding bodyweight drills, but I disagree once we introduce an outside load to the picture and start considering lever arms. Everyone should be able to meet minimal strength standards. But after the minimal standards are met, some consideration for body proportions needs to be made. Body weight, for example, can and will change — the length of someone’s tibia or humerus will never change after they are fully developed.

PART 3: ON “WORK CAPACITY”

Before going further, I need to clarify something. Strength is NOT work capacity. Work capacity isn’t defined in the dictionary. If you Google “work capacity,” the definition Google returns is from the CrossFit Journal, and is their opinion on what work capacity is. Not that their definition is wrong, but it is tailored to their concept of fitness.

“Work” is defined as an “activity in which one exerts strength or faculties to do or perform something.” Mel Siff (author of Supertraining) described work capacity as “the general ability of the body as a machine to produce work of different intensity and duration using the appropriate energy systems of the body.” Still not a definition, but we are now on the right track. When I hear the term “work capacity,” the voices in my head translate it to “the ability to express strength as long as needed, for the task at hand.”

“Strength” needs to be cleared up a bit also. Strength is the “capacity for exertion or endurance.” Many things go into expressing strength — physical fatigue, technique, strength, mobility, stability, motor control, posture, symmetry, neural fatigue, and several other factors I’m sure I’ve neglected to list.

Gray Cook wrote an article on his website not long ago discussing the term strength. To quote him:

“Work Capacity is what we strive for in human endeavors and strength is a key attribute that helps work capacity. At the right time, and the right place, lifting is one of the most effective things to promote work capacity, but if lifting creates inappropriate side effects or somehow undermines work capacity, then strength is an empty word. Anybody can say they have it.”

PART 4: COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS

If you have stuck it out this long, let’s begin to answer the question of “Why is this even important?” First, let’s look at two individuals who have to press the 48kg bell to achieve their Level II Certification. One is 6’ tall and the other is 6’6” tall. Let’s also assume they weigh the same.

The 6’ subject will press the bell 26” (I measured one of our staff members who is 6’). The 6’6” subject will press the bell 33” (21% further). The equation to calculate work is Work(J)=Force(N) x Distance(M). The weight (force) in our scenario is the same, but the distance varies, so the results are not surprisingly going to vary by 21% — the difference in the distance.

The taller subject with the longer press does 21% more work to press the same size bell over head. For meeting minimal standards, this 21% is not a big deal — from a training standpoint, this 21% is vitally important.

WARNING: NUMBERS and EQUATIONS AHEAD

Again, why does this matter? Taller means there are longer lever arms. Longer lever arms means there is a need for more stability (look at any large cell phone or radio tower — the taller it is, the further the guy wires reach out away from it). Add this need for greater stability to the fact that more work is done on each rep, and the result is a large difference in work being performed. A set of 10 presses with the same load will result in noticeably more total work being done by the 6’6” athlete listed above.

What if the 6’ athlete weighs 212lb and the 6’6” athlete weighs 230lb? Then relative strength can be an argument (or will be for the lighter person). In this case, the difference in relative size of the bell is 4% (50% of the bodyweight for the 212-pounder, 46% for the 230-pounder). Relatively, the 230lb person is doing 4% less work on each rep. Counter that with the 22% extra work they are doing because they have to press the bell further, and the result is still 18% more work for the 6’6”, 230lb athlete to press the 48kg bell overhead.

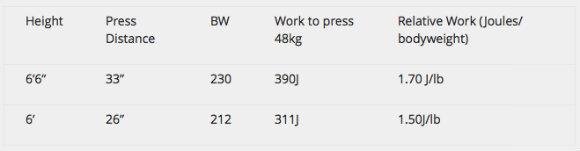

Another way to look at it is a much simpler conversation on relative work capacity (not strength). Work is measured in joules. This chart includes all the important numbers.

As you can see, relative work is still noticeably greater for the heavier athlete with a longer press distance. The idea of looking at the weight that is moved divided by bodyweight gives a very skewed picture of relative strength, and only works when the individuals being compared share the same body dimensions.

If these two were to perform a set of five one-arm kettlebell presses with a 24kg bell, this is how things would play out:

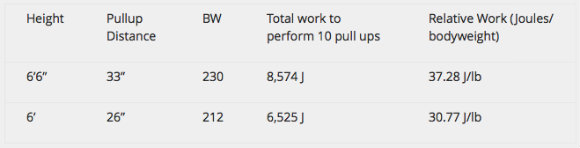

For a set of 5 reps, the longer press results in 22% less work being done by the shorter athlete. Bump that up to a set of 10, and the result will still be a 22% difference. But what if we looked at pull-ups?

All things considered, there is a total of 24% difference in total work being done. To do the equivalent amount of work, the lighter and shorter-limbed athlete would need perform 14 pull-ups. Relative strength really does a bad job at comparing work done between two individuals.

PART 5: STABILITY (NUMBER-FREE ZONE)

Again, why does this matter? How many people, when they begin training to press a heavy bell overhead, suffer from shoulder pain? Strength fixes a lot of things, but strength won’t necessarily fix this.

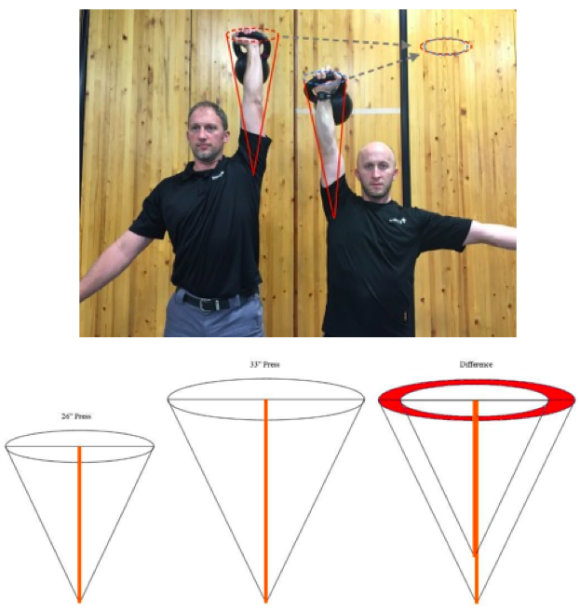

Remember the mention of stability from above? Stability work (lots of it) is important for the taller athletes with longer lever arms. Picture the “Cone of Stability” (I really don’t think that is a term, unless it catches on from here). Think of it as a an upside-down traffic cone — the taller the cone, the wider the base. In regards to stability, this concept means that the bigger the base the more wiggle room there is for things to be unstable.

In the image below, the red area on the far right indicates the extra wiggle room the person with the longer lever arm will have. The added difficulty to maintain stability while pressing a greater distance leads to a noticeable difference in actual work being performed.

When we discuss “relative” strength (strength in regards to body weight), we are using a metric that changes. If I can do 10 pull-ups at 230lb and then lose 30lb and do 15 pull ups, did I get stronger? No — I just have less mass to move. Body weight can be manipulated, lever arms never change. I may lose 30lb, but I still have to pull 200lb 33” to get my chin over the bar.

When we discuss “relative” strength (strength in regards to body weight), we are using a metric that changes. If I can do 10 pull-ups at 230lb and then lose 30lb and do 15 pull ups, did I get stronger? No — I just have less mass to move. Body weight can be manipulated, lever arms never change. I may lose 30lb, but I still have to pull 200lb 33” to get my chin over the bar.

My recommendation? Get screened using the FMS and address any mobility or stability issues present. Gray Cook and Dan John have released a DVD that discusses the importance of stability and how this can drastically affect strength and work capacity.

There are a lot of great pressing programs out there — Kettlebell Muscle, Pavel’s Rite of Passage, Return of the Kettlebell 2 — but they only address the press itself. Don’t get me wrong, these programs work for most people, but if someone has a stability issue or a work capacity issue that is their limiting factor (of they are in a group that will inherently need more stability). Going directly to these programs without addressing the stability needs will be problematic.

The need for stability is magnified in taller athletes who have longer lever arms, especially in regards to pelvic stability and trunk stability. Looking at the the FMS (specifically the trunk stability push-up, the rotary stability, and the deep squat) gives a picture of how stable someone will be to press. If you are tall, and looking to press half your body weight, then focus on getting those areas on the FMS to at least solid twos if not threes. If you have taller athletes you are training, same recommendation. The safe bet is that stability will lead to increased strength, but the opposite does not hold true — strength work will not lead to increased stability.

PART 6: WORKLOAD

Another consideration for training those athletes who are taller is that with each rep, they are doing more work. More work equals more calories burned. For the tall athlete who is trying to add muscle mass — which is every tall athlete — this has the potential to have a drastic affect.

If someone is not putting on muscle, what is the typical recommendation? Do more. But in this case, fewer reps may actually equal more muscle. Those hard-gainers may want to knock a rep or two off of each set — remember the numbers from above? A longer press can result in almost two times as much work being done compared to a shorter press. The cumulative affects of this could be what is sabotaging the muscle gains the tall, lean athlete is trying to make.

PART 7: COACHING

For complete clarity — I don’t think there should be special considerations for taller athletes in regards to the strength requirements at any StrongFirst Certification. Also, I’m not saying we (those of us on the big-guys platform) have it worse than those who are suffering from the prolonged affects of gravity. I am saying for those of us in the business of getting people strong, we may need to reevaluate how we do that for each athlete.

As I was training for Level II, Jeff O’Connor told me to come see him to work on my press once I could do get-ups with the 48kg. Surprisingly, once I could do that, the press was no longer an issue. (One of those WTH affects.) The explanation lies in the fact that the TGU is completely dependent upon stability from the ground up. (Those of you who read my earlier TGU article can recall the benefits of the TGU that I detailed.)

If those taller athletes you are training are stuck on a strength plateau, it might be the perfect time to change focus and emphasize stability work and work capacity (again, the Gray Cook/Dan John DVD discusses interesting ways to accomplish this). The key areas to address from a stability standpoint are:

• Stability overhead (finish position of the press)

• Stability in the rack position (start position of the press)

• Trunk and pelvic stability

How you choose to work on those areas is up to you — within the StrongFirst and FMS worlds there are plenty of options. The important thing is that anyone can get strong. However, by applying some very solid neurodevelopmental principles, anyone can also get stronger faster:

• Mobility before stability.

• Stability before strength.

• Patterns develop from the ground up/midline out.

• Strength develops with the patterns.

• More does not equal better.

I could add an additional ten-plus pages on these five principles and ten more pages by detailing how the fascial lines drastically affect this, but I’ve got to have topics for other avenues. Height (or lack of height) is not an excuse. Like many things in life, the path to “strong” will be different for everyone.

This is good

The amount of torque generated at a joint is markedly higher for the taller (more specifically – longer limbed) athlete.

To test this for yourself, have your arm by your side and bend the elbow to 90 degrees, now take a kettle bell and hang from the handle around your wrist, then move it half way up your forearm and note how much lighter it “feels” (even though the weight is the same). Now imagine what it feels like for a long limbed athlete whose wrist is another 4inches past your own!

I think a more germane factor would be limb length in relation to height/weight. This is colloquially referred to as the “ape index”.

Do quote myself – “I am not a mechanical engineer, physicist, or even someone that is somewhat good with numbers. The numbers I used were purely for the purpose of serving as an example to illustrate how height can affect the work”. I’m wrong, great job in pointing it out.

Take your mass and go run a half mile on a flat course. Then take your mass and go run a mile at the same pace on a flat course. Which one will you burn more calories and do more work? Assuming wind, the tides, your iTunes mix, etc are all the same – The mile. Another fallacy of the article is “tall people” – It should have correctly been labeled “those with long limbs”, my bad.

The point – when programming for long limbed individuals you need to take into consideration the extra work.

excellent article, will help me a lot. thanks

Brandon, thanks! Wish somebody wrote that article 27 years ago. At a lanky 6′ 2″ my constraint is actually having a slim pelvis — there’s only so much space for thick obliques & transversus.

You did not make up the term “cone of stability,” you just made it evolve! It is typically used in reference to your base of support for somatosensory balance while standing, but your use of the term certainly fits the bill if you’re using RTC as frame of reference vs feet.

As a not-exceptionally tall (6’3) but exceptionally lanky (6’10 wingspan) i can anecdotally vouch for the substance of the article. I’ve been lifting in one form or another for the better part of 17 years and much of that has been with training partners doing the same workouts. Consistently i have developed certain kinds of strength (presses specifically) much slower than my sometimes stubby limbed friends, while other exercises where limps are less relevant i keep up on par (such as with deadlifts). On the flip side, i swim faster than anyone in my pool though i’ve only ever taken one lesson, because i am so long, have big paddles (hands) that move the water a very long way with each stroke, think of Michael Phelps, with a 6’8 wingspan on a 6’3 frame.

Another point the author makes about environmental restrictions, I found the first pullup bar in 7 years that i can hang from with a straight body, rather than curling my legs. I knocked out 3 more pullups just being able to employ the GTG tensioning techniques rather than having to leave my lower body relaxed. Score!

Thanks for the article, Brandon!

I’m a tall girl for Brazil’s standard, 5’7″, and even here in US, I’m considered tall in Louisiana.

I understand why my Presses got so long to progress and my Pistol… Wow… Long legs, long way…

Like you said, it is not impossible, it just get longer and we have to work harder…

Thanks a lot!!

Hi Brandon, finally an article directed toward tall people! Being 6’5′ and 238 (109kg) I’ve found that certain exercises are much more of a challenge, especially the pull up and the press. However, following Simple & Sinister (reaching the Simple goal) I’ll now re-do the Rite of Passage as I now have excellent stability thanks to the TGU (so many TGU’s)! Even pull ups can become a ‘strong’ exercise with enough knowledge and practice, I’m now able to do 10 strict BW pull ups which I never would have believed I could 5 years ago. Thanks for excellent article.

it seems the physics of your argument is incomplete – the formula you chose to validate your argument, W= F x D, has a variable of Force, which you incorrectly define as weight. It is not, it is mass x acceleration. Now i’m not a physicist, so this will be crude, but i took enough physics 30 years ago to know that the acceleration variable, when dealing with a limb, changes based upon joint angles, muscle length and moment arm. A longer limb is equipped with a longer muscle which effects the amount of acceleration needed to move a mass and thus changes the amount of Force that needs to be applied. A longer muscle length may very well need less Force to move a weight than a short muscle length does, so even though the taller person needs to press the weight a greater distance to lock out, less Force may be required due to the length of the muscle, which could create an equivalent amount of work as the person with a shorter muscle. I havent done the study, so im not sure, but what i do know is that Phil Phister is 6’6″, Brian Shaw is 6’8″, and they seem to do OK lifting things overhead. i have been listening to athletes, short and tall, make excuses for why one person can do something that they cannot – genetics play a role, but i do not buy the tall versus short argument and neither does the weightlifting world otherwise class distinctions would be made primarily by height and not primarily by weight. i think if you are training someone you should pay less attention to height and more attention to type of build, endo, meso, ecto – when designing their program.

Weight actually is CORRECTLY defined as the force. You must match that force to hold the weight in place, neither falling or rising. Yes, as you lift the weight upward, you can accelerate it faster by using more force. Net force is the simplest variable. The longer lever arms, especially for a move like the overhead press, means that the torque of the weight will actually be GREATER than that for the shorter lever arm to overcome. The article didn’t say the long limbed person can never get there, he’s just saying you need to give special consideration.

Genetics and height DO matter a lot in feats of strength, and to say otherwise is somewhat absurd. I want to see a 6’6″ man win olympic gold in the still rings. You can reply, I want to see a man under 5’9″ win the strongest man competition. Different builds allow different strengths. See Dan John’s revelation on his “Scottish Hips” that allow him to excel at throwing events.

Coach an NBA basketball team in strength training and pay no attention to their height. See how long the gig lasts.

There is a difference between making excuses to not put in effort and being smart about limitations/special considerations.

Weight is a measure of the application of gravity to an object, the gravitational Force doesn’t change when you press, the Force applied to the weight you are trying to press changes based on the acceleration you create by the muscles and limbs of the working arm, and the length of the muscle affects the ability to accelerate. i don’t want to argue for the sake of arguing, but i think the topic is off base. What’s somewhat absurd (your word) to me is to say the training should be specific to height instead of specific to the trainees objectives, experience and functional screening – regardless of height. Go ahead – Coach that NBA team, take the Warriors, and tell me you are putting Stephen Curry at 6’3″ on a different program than Andrew Bogut at 7″0″, just because there is a height difference, you adjust their programs based on what assistance they need to best perform their role on the court. Your example of stability needs applies to all body types. If both Curry and Bogut are in need of stability work which could be helped by the get up, wouldn’t you have them both perform TGUs? Why would height matter? Please tell me how you would advise a 5″6″ inch swimmer, differently than you would advise a 6’6″ swimmer, both looking to gain torso strength for an upcoming 2 mile swim? Your training recommendations in the article seem on point, but they apply equally to shorter and taller trainees who present with similar issues.

I think perhaps too simple formula for work was chosen, but general idea is you need to spend given amount of energy (=work) to move the weight (say bell to not mix it with weight as a physics term) up by given distance. Since we’re dealing with simple moving the bell up in straight line, you can directly use change of gravitational potential energy of the bell, where basic “Ep = m.g.h” and delta Ep (=energy spent to move the bell) for pushing the bell “distance” up is then “distance * weight”. Which is exactly what the article states.

I’m not going into comparing strength of differently tall people, that’s way out of my field.

Great article–as a tall drink of water myself I’ve dedicated a lot of time to overhead pressing following level 1; progress is tangible (it doesn’t hurt!) but slow (stay right there, 48k, I’ll be back in a few years). Stability has definitely helped a lot, and having read the above I’ll be looking at whether more volume is helping or hurting.

You’ve made some great points, and I’m going to get screened straightaway–not to mention try and get a bit larger!

so, with other words: Tall athletes are bigger than smaller ones?!…