There are many reasons we want to stay out of glycolysis:

1. It can lead to acidosis (too much hydrogen ions) that affects the signals from our neurons.

2. Acidosis inhibits ATPase, which is needed to create ATP from creatine phosphate. We need that ATP for contraction and relaxation.

3. Acidosis blocks muscle contraction by affecting tropomyosin.

4. Acidosis affects calcium from being reabsorbed (so our muscles can't relax as fast).

5. Large amounts of acidosis damages mitochondria.

6. By using the aerobic system more, we become better at burning fat for fuel. We also shrink the glycolytic window (how much you need to be in glycolysis). Using the AGT style protocols builds a better aerobic base.

Thus, it seems that AGT training is on the right track. For the most part, our aerobic system can clean up the messy parts of the glycolytic system (uses the by-products of the glycolytic system to create ATP). The key is we need enough rest. If we don't get enough rest, then our body starts getting acidic as the aerobic system can't keep up.

As I read the awesome discussions, I see almost an aversion to going into glycolysis. There are great discussions about using the talk test and staying below the Maffetone number. I wonder whether there is a more nuanced view? There benefits to being slightly acidic and using the glycolytic system (e.g., it gets rid of less than optimal mitochondria, it can lead to hypertrophy). If we push into glycolysis and recover, then we can enjoy the benefits of the glycolytic system without the side effects.

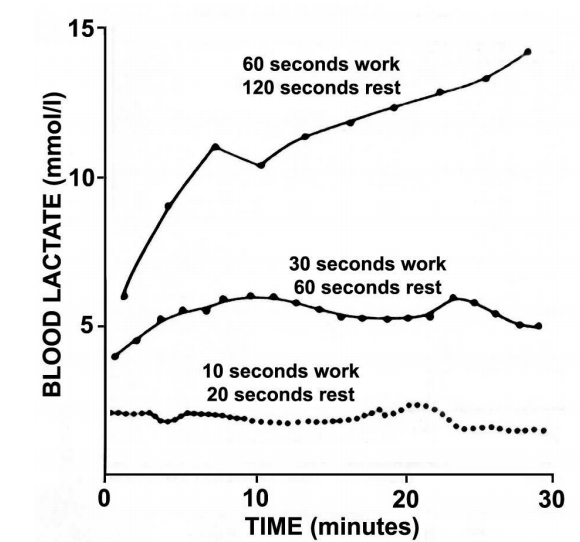

In the below graph, we see how different training affects lactate, which we can use as a proxy for acidosis (too much H+ accumulation). (above 4 is getting a bit acidic in most people). In the top line, sixty seconds of work pushes into glycolysis and the 120 seconds of rest is not enough to stop the accumulation. The second work to rest interval of 30 seconds of work and 60 seconds of rest is slightly acidic, but does not get too far out of control. The bottom line shows much of what we want to accomplish with AGT work. We do short amounts of work with enough rest to do it again.

About two years ago, we experimented with a protocol that included about 30 seconds of heavy swings (think 25 swings with a 48kg for a male). There was then a 10 minute rest period (maybe 4 to 5 sets). During the 'rest' we did a Plan Strong styled press program of a few sets of presses. People on this style of plan experienced a great deal of hypertrophy and fat loss (they were also frustrated with me with the super long rest intervals). By pushing into the glycolytic zone a bit more, but not staying there a long time, people benefitted from the effects of a little bit of acidosis, but did not have the long-term problems with too much.

My main point in writing this was that we don't have to be too afraid if we go over the Maffetone number or can't do the talk test after every set. We can create cycles of training where we are strict on our Maffetone number and other cycles where we touch into glycolysis and then back out. Furthermore, our peaking programs likely need to be glycolytic in nature to prep us for events (but a peaking cycle should be quite short and only once in a great while)

I am likely going to use this as a start to an article (so feedback is appreciated). We also cover this topic in Strong Endurance and All-Terrain Conditioning seminars.

1. It can lead to acidosis (too much hydrogen ions) that affects the signals from our neurons.

2. Acidosis inhibits ATPase, which is needed to create ATP from creatine phosphate. We need that ATP for contraction and relaxation.

3. Acidosis blocks muscle contraction by affecting tropomyosin.

4. Acidosis affects calcium from being reabsorbed (so our muscles can't relax as fast).

5. Large amounts of acidosis damages mitochondria.

6. By using the aerobic system more, we become better at burning fat for fuel. We also shrink the glycolytic window (how much you need to be in glycolysis). Using the AGT style protocols builds a better aerobic base.

Thus, it seems that AGT training is on the right track. For the most part, our aerobic system can clean up the messy parts of the glycolytic system (uses the by-products of the glycolytic system to create ATP). The key is we need enough rest. If we don't get enough rest, then our body starts getting acidic as the aerobic system can't keep up.

As I read the awesome discussions, I see almost an aversion to going into glycolysis. There are great discussions about using the talk test and staying below the Maffetone number. I wonder whether there is a more nuanced view? There benefits to being slightly acidic and using the glycolytic system (e.g., it gets rid of less than optimal mitochondria, it can lead to hypertrophy). If we push into glycolysis and recover, then we can enjoy the benefits of the glycolytic system without the side effects.

In the below graph, we see how different training affects lactate, which we can use as a proxy for acidosis (too much H+ accumulation). (above 4 is getting a bit acidic in most people). In the top line, sixty seconds of work pushes into glycolysis and the 120 seconds of rest is not enough to stop the accumulation. The second work to rest interval of 30 seconds of work and 60 seconds of rest is slightly acidic, but does not get too far out of control. The bottom line shows much of what we want to accomplish with AGT work. We do short amounts of work with enough rest to do it again.

About two years ago, we experimented with a protocol that included about 30 seconds of heavy swings (think 25 swings with a 48kg for a male). There was then a 10 minute rest period (maybe 4 to 5 sets). During the 'rest' we did a Plan Strong styled press program of a few sets of presses. People on this style of plan experienced a great deal of hypertrophy and fat loss (they were also frustrated with me with the super long rest intervals). By pushing into the glycolytic zone a bit more, but not staying there a long time, people benefitted from the effects of a little bit of acidosis, but did not have the long-term problems with too much.

My main point in writing this was that we don't have to be too afraid if we go over the Maffetone number or can't do the talk test after every set. We can create cycles of training where we are strict on our Maffetone number and other cycles where we touch into glycolysis and then back out. Furthermore, our peaking programs likely need to be glycolytic in nature to prep us for events (but a peaking cycle should be quite short and only once in a great while)

I am likely going to use this as a start to an article (so feedback is appreciated). We also cover this topic in Strong Endurance and All-Terrain Conditioning seminars.