Co-authored by Jonathan Pope

Special operations selection courses are not just physically challenging. They’re also incredibly mentally and emotionally stressful. One of the most common ways of creating this stress is to shroud students in a constant cloud of ambiguity. You never know what’s coming next, how long it will last, or how much more until before the day is over. You’re never even sure if the day is going to end or if you’re just going to be there until the next morning. You carry your ruck to the next waypoint and have no idea how far away the one after that will be. And you need to move as fast as you can to make a cutoff that you have no way of knowing. You do pushups until the instructor says to stop doing pushups. You swim sprints until you think it’s impossible to continue. And then they say “Do it again. First man, enter the water!”

Most of the people who quit in selection aren’t carted off in an ambulance. They still have blood sugar and oxygen to spare. The pain they feel, while excruciating, will fade within a few days but their mind no longer believes that their body can keep going.

There are many things that make a successful special operator, and you need all of them. This is one of the most important concepts in training special operators. The most important variable in the system at any given time is the one that’s most limiting. It doesn’t matter how good you are at exercising if you crack mentally when you don’t know how much longer the next run, swim, or beatdown is going to last.

Manage Stress

Successful special operators are those who effectively manage their stress responses. The physical workload is only one component of the stress your body and mind feel. There will always be a “mere physiological demand” to an effort. But we have the ability to control how much we add to that stress load with our emotions, thoughts, and opinions. Anytime we’re training, we’re building patterns and associations around every aspect of what we’re doing.

We use open-ended workouts to manage some of the associations built through physical training. Unlike traditional gym sessions, you don’t know how long open-ended workouts will last. In a normal training session, your brain calibrates your effort and perceptions of fatigue to a known, fixed quantity of work. “This is what I can do for five sets of five.” Open-ended sessions take that certainty away. The association that your brain must build with the activity becomes, “I can sustain this for as long as I have to.” You’re training yourself to be ok with not knowing.

Our perceptions of predictability and control drive our stress responses. When we know what a situation is, how long it will last, and that we have what it takes to handle it, it’s not a big deal. When we can’t answer the question, “Do I know what this is, and do I have what it takes to cope with it?” our stress response ramps up to ready us for a threat. Open-ended workouts change this dynamic. They create the association that you can handle this, no matter how long it goes on. You’re no longer dependent on knowledge of a fixed endpoint to regulate your stress response.

What is Fatigue?

While it’s easy to think of fatigue as a mechanical process, like being a car that runs out of gas, the reality is far more complex. Our perceptions of effort and fatigue are more like complex, predictive emotions. Your brain is continually processing an incoming stream of internal and external data including body temperature, hydration, and glucose levels as well as factors like humidity and air temperature. That information combines with predictions based on your prior experiences in similar conditions.

For example, your brain calculates how hard it will be to run four miles based on your previous experience with four-mile runs. If it’s hotter and more humid than usual, you will start out running at a slower pace than normal. Your brain compares past experience to present conditions and adjusts your output levels to make the same distance sustainable under more taxing conditions. Fixed-quantity workouts play a big role in this. They feed into this appraisal process and create associations of limitation. When we do a workout knowing that it will be for precisely 75 repetitions, or for 10 minutes, or any other known quantity, we’re training our internal algorithms that those numbers represent our limits.

Then, if we find ourselves doing something in which the effort must go on longer than we’re used to or than we estimated, our brain doesn’t know what to do and puts the brakes on. This compounds the stress response that we produce due to the loss of perceived predictability and control.

Open-Ended Workout Program Design

Designing an open-ended workout is only limited by your creativity. These sessions work well with variations of the anti-glycolytic protocols that Pavel describes in Strong EnduranceTM. You can extend the capacity of your aerobic and ATP-PCr energy systems for a very long time. You’ll hit a wall much faster if you play these games with anaerobic output.

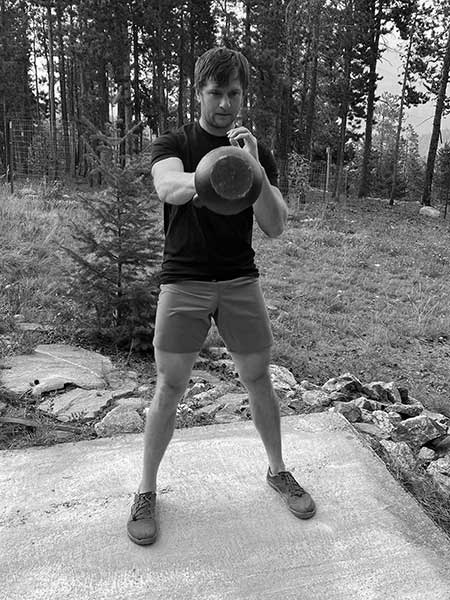

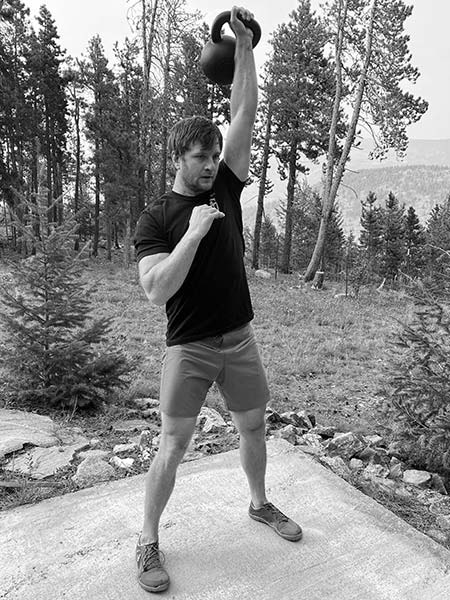

The “Coin Game” is one of our favorite methods. Here’s the workout:

Grab a handful of change out of your loose coin jar without looking at it and put it one pocket. If you’re not wearing something with pockets, find something else to hide them in. The coins represent how many sets you’ll be doing. One coin equals one set of five swings. After completing each set take a coin out of your pocket and place it in your other pocket or some other container that you can’t see inside. Keeping them out of sight both before and after each set means you never know how many sets you have to do nor how far yet to go. This increases the ambiguity and maximizes the intended effect of the training.

Rest a bit, then do it again. Keep moving as fast as you can while keeping your heart rate below about 150 bpm, or while maintaining your ability to breathe solely through your nose. You won’t know how many coins you have left, and after a while you’ll probably lose count of how many reps you’ve done. As you go, you’re teaching your brain that this level of output can be sustained for as long as needed. That becomes the baseline that you are improving over time.

Once you’ve emptied your original pocket of coins, the workout is over.

You can play with many variations of this idea. Pick a compound exercise. Most kettlebell movements like snatches and swings are great for this. It’s also useful to work in things like pushups, rowing variations, and pullups.

Select a rep-range that gives you about ten seconds of work or less. This could be things like:

- 3 reps per side of a reverse lunge with a racked kettlebell

- 3-5 goblet squats

- 5-10 swings

- 1-2 pullups

- 1 get-up (it’s fine if this takes more than 10 seconds, or consider doing a partial get-up)

- 3-5 pushups

- 2-3 reps per side of a heavy single-arm dumbbell row

- 3-5 ring rows

- 1 snatch per side

You get the idea. Be creative. Balance your movements between pulling, pushing, squatting, and hinging and be sure to include some rotational and lateral movements.

Music can also work well for dictating open-ended sessions. Here, you’re using a shuffled playlist of music. You decide (or a dice roll decides) how many songs this workout will last. The random duration of songs in the playlist will make it impossible to know exactly how long you’re going for. You can do this with either longer sustained efforts such as time on a bike or with a ruck, or as a way to measure the total duration of high-volume anti-glycolytic work.

Session Examples:

Option #1: Every minute, on the minute, do one deadlift, 3-5 pushups, and 1-2 pullups.

Option #2: Every 30 seconds, do one snatch per side.

Set your weights at a level that you’re confident you can sustain for a long time without risking injury.

The next time you do these you could shuffle the playlist, pick a different number of songs, or both. You’ll no longer be able to mentally set a limit to the number of sets you’re doing. You just keep doing them until it’s over.

Training partners are also great for open-ended workouts. One day, you have the plan and know what’s going to happen and how long it will take. The next workout, your partner has the plan and you’re in the dark.

Conclusion

Open-ended workouts are a useful component of a training plan but shouldn’t comprise your entire training plan. There is value in using fixed sets, reps, and durations. By striking the right balance of fixed training to open-ended training, you can develop a mindset that’s resilient in the face of uncertainty. Meanwhile, more structured training allows you to test and develop capacities that benefit from precise management of volume and intensity.

Jonathan Pope, co-author of this article, is a strength and conditioning coach based out of Denver, Colorado with over ten years of coaching experience and a BS in Exercise Science. Along with Craig, he co-founded Ethos Colorado Training Center in 2010, where he is the lead coach and oversees operations. Jonathan also works with Precision Nutrition as a coach where he develops coaching strategies used with thousands of clients every year. When not working he can be found chasing ski mountaineering objectives all over the world or competing in Brazilian Jiu Jitsu. Jonathan co-wrote Building the Elite: The Complete Guide to Building Resilient Special Operators with Craig Weller.

I really like this concept. I’ve been using at home since gyms in my area are closed again. I downloaded a random timer app that lets you set a minimum and a maximum time so I can make sure it works with my schedule but still varies greatly. It also gives the option of setting a random work and ret time so I may try using that for cardio intervals.

Quality posts is the secret to invite the users to pay a quick visit the

website, that’s what this site is providing.

Very interesting concept – adds a mental aspect that as a civilian I’d personally never thought of.

I would imagine, if you ran a protocol like this with “regular folks”, there would be a drop in intensity – if you’re starting a session where you don’t know when it ends, you’re naturally going to try to conserve energy up front. Regular people are missing the aspect of “need to move as fast as you can to make a cutoff that you have no way of knowing”. Maybe not an issue for special operations trainees, I imagine they are pretty self-motivated.

Any thoughts on how to avoid that intensity loss with a group of civilians?

Think of it more in the sense of long-term adaptations rather than workout-to-workout performance. If your sole goal was to get someone to do something as intensely as possible in a single workout, you wouldn’t use this method.

First, you can adjust the weight that they’re using if you have a sense for what they’re capable of. That gives you control over intensity in that sense. You can also control density by prescribing the work to rest rations. The only part they’d be blind to would be the total volume.

And yes, people will likely slow down and hold some in reserve when they don’t know how long the workout is going to last, but that’s where multiple sessions and learning/adapting over time comes into play.

Let them do whatever they do in the first session and then when it’s over, immediately run a feedback loop. Have them reflect on the workout and what they were thinking and feeling during it (you can also ask them during the workout if you’re around). Ask them to evaluate their perspective during the workout and how they would adjust things if they did it again based on what they know now about how they performed throughout the workout and how they felt when it was over.

In most cases, people start to form a better sense for what their “for as long as I have to” pace is, and can begin to calibrate that pace upward as they develop a sense of predictability and control over the workout – not by knowing how long it will last, but by knowing that they can last as long as they have to.

Thanks for your response – makes sense

As I have gotten older I find it more difficult to find the motivation or attention span to complete basic gym workouts. A few years ago I began a minimlist approach to fitness, using exercise programs outdoors on random days and times. The change has been fantastic. Thanks for some new ideas.

Thank you for this article! In a week how many days would you program a workout like this? Tanks in advance.

Typically once or twice per week. For example, we may have someone do a coin game with KB split squats as part of a strength workout during the week, and then do an open-ended ruck with a training partner on Saturday.

Thank you!

Hello,

Great article. Great workout.

One question. In option 1 you recommend to do the exercises in rotation? Or all EMOM? The reason I am asking is because all three most likely will exceed 10 seconds.

Thanks

I’d do them all together, one round EMOM. The total duration is just over or right at the approximate theoretical limit of maximal output from the ATP-PCr system, but since you’re doing different movements with different local muscular demands with a tiny bit of rest in between each thing (as opposed to sprinting up a hill for ten straight seconds) I don’t think you’d meaningfully blow past that energy system barrier.

Those exercises are somewhat arbitrary examples, of course, and with any individual you’d need to make sure that they had the movement fidelity to sustain them under fatigue, the work capacity to handle that much volume in a workout, etc.

That’s also assuming that you could do a deadlifts, pushups, and pullups in roughly the same place. If you had to run all over the gym to go between a pullup bar and a deadlift platform you’d probably want to structure it differently.