The Kettlebell Mile is the product of a two-decade long search for a way to simultaneously train strength and aerobic capacity. It seems so obvious now, but the best ideas are seen as such only in retrospect. I had much learning and tinkering to do first but finally, the science and my experience (and that of others) converged around this simple idea. What follows is a brief description of that process.

I have been interested in load carriage fitness for more than twenty years. It started in 1997, when I attended the Marine Corps Mountain Warfare Training Center’s Wilderness Medicine course. The training center is at an altitude of about 8,000 feet and terrain in the area rises to above 10,000 feet. We ran in the mountains every morning, and then packed up a bunch of climbing gear along with medical supplies and survival items, and marched uphill for several miles to the training area with our loaded backpacks. I just happened to be a middle-of-the-pack guy for both the runs and the rucks, so I was able to notice something interesting. The guys who were out front on the runs were off the back on the rucks and vice versa. The skinny runners were hurting as soon as you put a pack on them but the six-foot plus big guys who suffered on the runs were crushing everybody on the rucks. One big, tall guy was dropped in the first half mile on all of the runs. You would assume from his performance on the runs that he showed up for the course in poor shape. However, he was up front for the rucks, effortlessly pushing the pace. I kept expecting to see him drop, but he didn’t. This whole phenomenon was quite a surprise for me. I knew that something interesting was happening so from that point on, I started to pay attention to the research on load bearing marches.

My first clue about what was going on was from my own perceptions of the difference between the rucks and the runs. My limiter on the run was a sense of whole-body fatigue and breathlessness. However, on the rucks, I wasn’t completely out of breath. The issue was the tremendous amount of fatigue in my glutes and especially my hamstrings. I did not have the muscular power to push the pace any faster, though I still had some cardiovascular reserve. The effort during the ruck was obviously aerobic due to the duration (over two hours) and the fact that my heart rate and breathing were significantly elevated. However, my performance was limited by muscular fatigue, not by my cardiovascular capacity. Was this why the big guys did so well on the rucks compared to the runs?

When I finished the course, I began to dig into the research literature on load carriage. Fortunately, the U. S. Army has sponsored lots of research on the topic. There were some interesting, and somewhat surprising findings among the research papers. Researchers found that when ruck loads exceed 40kg (typical military combat load):

- Unloaded run performance does not seem to be related to ruck performance.

- Run training alone has little impact on ruck performance.

- Strength training alone improves ruck performance.

Let’s pause to contemplate these findings for a minute. So far, the research seems to indicate that strength is more important than cardiovascular fitness for heavy ruck performance. If you have to choose between running and strength training, you should choose strength training to improve your ruck performance for a typical military combat load. There were a couple of other interesting findings though.

- Strength training combined with a running program resulted in greater ruck performance than strength training alone (or running alone).

- Heavy ruck training transferred performance benefits to light (but longer) ruck events but not vice versa.

- If participants engage in a strength training program and a run training program, there is little benefit from engaging in ruck training more than once per week.

The picture that began to emerge was that at heavier loads (i.e., greater than 40kg), strength is favored over aerobic capacity. However, it is obvious that as loads get lighter, you will reach a point where aerobic capacity is favored over strength (i.e., at zero load). Somewhere in the middle we should theoretically be able to find a crossover point where strength and aerobic capacity are equally favored in determining ruck performance. If we could test, and train near that crossover point, we could test and build strength and aerobic capacity simultaneously with one simple task.

As a scientist and a consultant to the U. S. Navy and Marine Corps, I was interested in finding that crossover point because it might be a simpler, more effective test of military fitness than running, sit-ups, pushups, and pullups commonly employed by the services. It could provide a single, simple metric to determine if a training program was producing “tactical fitness.”

I never had the chance to formally test these ideas during my career, but I had plenty of chances to do some informal testing while serving as the staff exercise physiologist at the U. S. Naval Academy. I had a chance to work with many midshipmen who had load carriage task requirements (Infantry Skills Team, Special Operations Team, USMC TBS, SEAL Screener, EOD Screener, etc.). Though the U. S. Army recommends that soldiers never run with a loaded pack, the reality is that this is common, and even necessary for some screening events. It became obvious that run gait was severely hampered when loads exceed about 35% of bodyweight. Most people could only shuffle along with heavier loads. On the other hand, loads of less than 20% of bodyweight seemed to be relatively easy, even for distances of four to five miles. So, it seemed as though a good, moderate load that was challenging, but tolerable for reasonable distances and at a reasonable pace (fast walk to a slow jog) was between 20% and 35% of bodyweight.

Around this time my interest in load carriage began to intersect with my other interest, run gait analysis. I was observing and filming athletes running on the treadmill during VO2 max testing in my lab. The most consistent run gait flaw I observed was nonsupport side hip drop with run cross over gait. This happens when the gluteus medius and gluteus maximus (along with all of the abdominal trunk musculature) fail to stabilize the hip when the foot impacts the ground. This results in the hip moving outwards laterally (on the foot/ground contact side) and excessive hip drop (on the other side).

To compensate for poor hip stability, runners adopt a cross over gait style. To envision run crossover gait imagine if we drew a chalk line on the treadmill belt (I actually did this), and asked runners to keep the line centered as they ran. In a “normal” gait, the second toe (the one next to the big toe) would not cross over the line. In crossover gait, the second toe, and often, the whole foot crosses over the line on both feet, so they are crossing over the line with each step. The crossover is happening because the hip is moving out laterally. It all starts with poor hip stability.

As a result of this insight, I started working with these runners to train hip stabilization. One obvious choice was to load a correct gait pattern so that we could build hip stability and strength. We started with loaded backpacks and found that they could feel fatigue in the gluteus medius and maximus when they concentrated on stabilizing their hips during the crossover gait drill (walking or running along a line on the road without stepping over the line with either foot), so I knew we were on the right track.

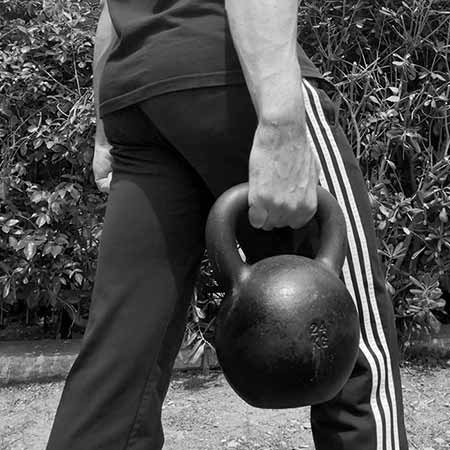

I made one small adjustment that seemed to have a very positive impact. Because I was working with runners, not infantry soldiers, I switched from a loaded backpack to a kettlebell held in the suitcase carry position. Because this is a single sided carry, much more trunk musculature effort was required to carry a similar load. In one move we were addressing most of what was causing the flawed run gait in most of the runners. Unlike traditional loaded carries, which are usually 10-50 yards, we wanted longer distances because we were trying to build both strength and endurance so that we could improve hip stability and run gait. As a bonus, it is safer than running with a similar load because when you fatigue you can simply drop the kettlebell and rest. You can’t do that with a backpack. Also, the load seems to be cushioned more in the suitcase carry position than when it is loaded directly on the spine with a backpack.

After some trial-and-error, we settled on a simple session of moving on foot, carrying a kettlebell for one mile—the Kettlebell Mile. It was easiest to use the common sizes, 16kg for ladies and 24kg for gentlemen. That generally put us in the 20% to 30% of bodyweight range. As you would expect, skinny runners with little strength and big, strong guys who are poor runners generally do not do as well as good runners who also have some strength or big, strong guys who can also run. We seemed to have stumbled on a load and distance that is in the vicinity of the aforementioned crossover point where strength and aerobic power are equally important and because of that we would expect a runner with a bit of a strength base and a weightlifter with a bit of a run base to do equally well. Performance on this simple test seems to be a good indicator of the kind of fitness that first puzzled me at the Marine Corps Mountain Warfare Training Center years earlier. It is also a great training session for runners (to train hip stability) and those who are looking for that “middle of the road” fitness, somewhere between strength and endurance (i.e., tactical athletes).

Is this a test or a training session? It can be both or either. Consider what it would take to do well at this simple event. If, for example, a person can cover a mile in nine minutes with the prescribed kettlebell load, what kind of “what the heck” effects might you expect? Lots of good things probably. If doing this as a training session, it is best done, at most, once per week, as with rucking, when combined with a strength training and running program. Use simple progressive overload by increasing either the distance or the load initially, until you can complete a mile with the prescribed weight. Then start to work on speed. As a test it can be done periodically to gauge progress. I also think it has lots of potential as a competitive event.

Most people are going to walk it initially. A fast walk for most people is going to be at about 4 miles per hour or 15 minutes per mile (really moving). So, if a person can keep moving, switching hands on the go, they can complete it in 15 minutes while walking fast. Those who can jog with it might manage 11-13 minutes. 9-11 minutes is very good. Under 9 minutes is very, very good.

Performing the Kettlebell Mile is simple. Find a measured distance that is relatively flat. It can be a track, an out-and-back course, or a point-to-point mile. Anything works. Simply carry the kettlebell in the suitcase carry position, switching hands and stopping as often as you want (but the clock keeps running). Cover the distance as fast as you can. You can walk, jog, or run. No gloves are allowed but you can use chalk. I like to hook a chalk bag to my shorts with a carabiner and I also carry a sweat rag tucked in my shorts for when it is really hot.

The right shirt for hard men and women to train in

I’ve gotten lots of feedback from people who have tried the Kettlebell Mile and the general consensus is that it just feels right. It seems to be the right load, distance, and type of effort. Much like the first time I tried Simple & Sinister, the first time I tried the Kettlebell Mile, I knew I was on to something. In his bestselling book, Christopher McDougall argues that we were born to run. I would argue that we are also born to carry things. This is a simple, primal move. But don’t take my word for it. Grab a kettlebell and give it a shot and see if it feels right for you.

Build an amazing capacity for adventure

All-Terrain Conditioning™ Course

in person or online

Great article Mike! I hope I’m not too late for a response but I was wondering how you’d go about improving your ruck times then? I’m probably just missing something but from what I’ve gathered heavy rucks for short distances but how short? Thanks a ton for any help you can give!

As an aside, can’t find your email address from last year. You gave me some tips to pass along to my son to prep for the Navy’s OCS. The tips were spot on and he graduated last weekend.

Hi! I just moved in to a new house and the streets here are rolling – perfect mix of uphill and downhill streets. Do you recommend starting with 24kgs or would you recommend starting at a lower weight? I currently own a 24kg and a 12kg bell. Thanks! P.S. I’m a kettlebell enthusiast living here in The Philippines.

Try your 12 kg kettlebell first to see how it goes. If that goes well then you could try the 24k. You don’t have to do the whole mile the first time you do it.

Finally, I can put my kettlebell to use. What a creative way. Thank you so much

Hi Mike,

I’m one of those skinny runner-types (160-ish). I’ve been using your Tactical Template to train pretty religiously, so I have built some degree of strength and endurance as a result. I tried the mile (1.1 miles, actually) and walked it in about 18 minutes with a 22 pounder. HR stayed around 85-90, so definitely could push much harder. What about doing the mile with a KB in each hand; say, 2 22-pounders? Would take away the option of switching hands but curious regarding your opinion on this. Thanks, Bob Moseley, Annapolis, MD

Hi bob. The unbalanced load is one of the things that’s best about this task. Holding a kettlebell any chance would balance the load. I prefer one side only in this case.

Thanks; makes good sense.

An actual suitcase full of rocks or a heavy kettlebell annoyingly tends to bang against (or at least graze against) my leg while running. That’s why I prefer slightly bent steel bars for heavy suitcase carries . The bend keeps the bar from rolling out of your hand and makes it easy to balance. It is a joy to run with. I got my bars from the Steelyard on Columbia Blvd here in Portland, Ore.

I use a slightly bent 55 lb (25 kg) bar for my suitcase carries. The bend near the center of gravity makes it easier to grip and balance. Each interval is a 30 sec round trip up and down a steep section of a grassy hill. Weighted partial rep pushups (3 to 1, bottom to top) fill in part of the time between carries. This variation and the time spent donning and divesting the weighted backpack give enough rest time to make the whole thing alactic. I like to train this way about two hours per week. But now I’m curious to try the kettlebell mile.

I tried this today after work. Doing it in 100 degree heat and relatively high humidity turned this into a mental challenge as much as anything. I’m glad you mentioned the towel. Mine fell out from my pocket twice and I required myself to circle back without putting the KB down. But it was needed for all the sweat pouring into my eyes.

I found this to be superb training session. Thank you for the article.

Right on! Glad you enjoyed it

Tried this twice.

I’m coming off of an injury…

1st time I attempted this I got once around my block with 12kg and had to put the bell down in the middle of the block AND at the beginning of each “corner”(6 times).

I was bummed as this was 1/3rd a mile.

That’s all I could do and it took me 19minutes to do that 1/3rd mile.

Unacceptable.

I’ve been training swing-squat-curl-press-reverse lunge chains easy strength program style daily…

I tried again yesterday.

3 times around the block=1 Full mile.. One 15 second break.

Completed in 17 minutes. 16kg

Here’s to the ALMIGHTY “what the heck” effect!

54year old woman. I will continue until I shave more time off then I’ll bump the weight up again.

This is fun. 🙂

Anybody who thinks this is fun is my kind of person! Keep at it.

As an ancient beginner with lots of issues—for example, I can’t do swings or deadlifts—I found this amazing and encouraging. I used to walk a 15 minute mile, so now being able to do that again is a goal, because it seems doable. I just did my first try and turned around at 7.5 minutes, even though I was quite short. So I will start pushing next time and, when I get there, I will add a little dumbbell.

Because I discovered that I can’t swing it, I have already been using my 20 lb kettlebell for suitcase carries around the house. I am so looking forward to the day I can put it together with a 15 minute mile. I may never get Simple, but I may get this.

Thank you so very much for all your work.

Lisa, thank you for your comment.

I encourage you to join our forum and post a bit more about yourself, and your injury history and restrictions. Perhaps we can offer some guidance as to what other things you might be able to do. The forum’s a great place and I hope you’ll join us. https://StrongFirst.com/community/

Steve Freides, Forum Moderator

Love this. Thanks for sharing.

First attempt in my local park yesterday. Okay, my time wasn’t great but felt good afterwards and woke up this morning with a bit of muscle soreness in the traps, forearms and triceps so you know you’ve been challenged. Really good additional dimension to an overall conditioning and strength programme

Hi Mike, Great article. I’m excited about challenging myself to the 24kg kettlebell mile. However, I have some concerns. I realise this may sound wimpy but I wanted to get your thoughts on keeping the discs in the spine safe while doing this run. Will all of the weight on one side of the body, could the back discs get too compressed on the weighted side and bulged on the non-weighted side? While I’m guessing there is an element of this in a suitcase deadlift, that exercise is a very easily controlled movement. It seems like it could be difficult to keep the spine straight when running, along with the constant impact each time the foot hits the road. Would a 2 handed run be safer to distribute the weight and prevent the possible bulging of the back discs?

Start with a lighter kettlebell and see how it goes. Personally I have no problem with it even with the history of herniated discs in my neck and lower back. I’m careful to maintain an upright posture and keep my core tight throughout. But a safe way to begin is to start light and gradually work your way to the 24K and see how it works out for you

Hi Mike, Just seeing this now. The strongfirst insta post brought me back here. Thank you so much for the response. You have put my mind at ease. I happen to have a 12kg kettlebell so will try the mile with that first before building things up to 24kg.

Excellent and interesting read. I applied it yesterday. Went for a Half Mile jog (it felt fast, but was actually just under 7:30) with my 24kg bell. I’m 26 and feel like I’m generally in good shape… maybe a little weak but I’ve never struggled with anything aerobic.

Boy, was that tough!! The crossover gait was clearly evident. How do I strengthen my hips so I don’t do that?? Thank you!!

I really like single Legget squats for that purpose. Pistols are fine too but I have a hard time doing them and a hard time teaching them so I just use a simple single legged box squat. Works great. Also single legged jump rope. But the beauty of carrying a kettle bell is that form seems to be self-correcting as you get stronger from simply walking with a load and keeping good posture

Love this!

As the saying goes, “Everything genius is simple”

Is there any shame in, or anything wrong with, trying this out on the treadmill? I only ask as my trail ride may get rained out today, and I would love to give this a try today I think.

No the treadmill is just fine. If you put in a 1% grade it will be the same effort as doing it outside on flat ground

Did this yesterday with my 24kg., 180 lbs moderately fit. 19 minutes for the mile. Had taken the dogs out for a short run prior to attempting. Definitely can feel the workout today. Was a good challenge.

maybe you don’t need compliments … it’s a beautiful article on a very complex topic that has always been much discussed. thanks for sharing your tremendous experience. and thanks for the test tool

I have been in the Strongfirst community for many years now. A personal opinion, but this is simply the best article I have read to date. I would be tempted to use the term groundbreaking. Excellent.

So would I.

This is a great article – thanks so much.

What for you are the key form indicators when performing the suitcase carry over the prescribed distance?

Just keep a reasonably upright posture and keep your core tight. Your shoulder should be relatively level.

Wow, great article!!!

I’ll try it in todays lunch break.

Actionable info combined with the background story, no sales pitch. Great. Some articles heer scratch the surface just a little, to tease for the courses. I am totally in line with that, Stron First is a company.

But this type of free content makes me come back and back again!! Thank you Mike.

Is the prescribed weight always 16kg for women and 24kg for men? Also, can the KB Mile be done while rucking, or should it be done separately?

Really you can use any weight you want. Sometimes I go lighter and faster or heavier and slower. The 16k and 24K are just standards. In training you could do whatever you want

This was a good find for me- my walk to work is a mile (so 1 mile x 8 walks each week). I’m looking forward to adding suitcase carries to my walking/running/sprinting options.

I always did better on pt tests after a cycle of humping a heavy ruck ( road marches, and humping the boonies) than just running alone. I was always puzzled why pt was centered on running. I always felt strength training was better than constantly running all the time, but i oftened wondered why strength training was never combined with running, but I’m talking mid 1970’s.

this is absolutely FASCINATING!!!! Thank you for the work you put into observing, testing and sharing this!

If ,a newcomer,

a small amount of strength training,

no running training.

How many times a week is the Kettlebell mile?

Once per week.

Sir, great article, really. I see an opportunity for me to challange myself in this kind of way. What do you think about combining the Kettlebell Mile with rucking for someone who is preparing for a selection/qualification to special forces? There will be lot of rucking and a half marathon with the ruck load.

Rucking would be more specific but throwing in an occasional kettlebell mile would be good.

Very well presented, sir. I love the simplicity of this, arrived at by actual observed trial and error.

In my 22-plus years in the military, I deployed with troops that could max out their PT tests, but couldn’t actually do their real world tasks. Conversely, there were below average testers that you would want in the field because they could get things done.

Your observations rang true to my experiences, and now I understand why. I’ve been retired for about as long as I was in, if only I had this article back then.

Thanks for sharing this valuable information.

If you look into the ethnographic record of the carrying habits of hunter gatherers (modern and historical) you will find as follows. Babies were carried on trips to gather. Gathered fruit and vegetables are carried back to camp. The killed game was carried back to camp – unless it was elephant sized and then the camp was shifted close to it. When it is time to move to new hunting\gathering grounds tools, hunting implements, furs etc and babies are carried. Mimicking the core elements of carrying is undoubtedly part of a generalist program that is aligned with our hunter gatherer past (ie. as you wrote).

Mike… the bit about crossover gait is lighting up my brain right now. I’ve never seen/heard of that as a gait issue – gait analysis has always been a weak area in my learning. Tried the suitcase carry with a 20kg (I’m 64 kg) and was amazed at what happened – immediate crossover. Very interesting as I “pass” most to all of the typical tests (FMS, YBT, etc.) regarding dynamic stability – I struggle mostly with rotary stability – but have trouble with the single leg deadlift sometimes. Did this walk for ~3 minutes. Went back and check rotary stability – clean. Single leg deadlift – clean and smooth. Can’t wait to test this out with some of my athletes who have struggled similarly.

Thanks,

Wes

Wes, take a look at the stuff by “The Gait Guys” on run crossover gait. It is excellent.

Will do. Thanks Mike

Great to see you’re still interested in the game, Mike. Hope you guys are well and enjoying life. Hit me up sometime.

Al