In the 1950s, medical research was primarily done on Caucasian males. It was thought it would be simpler to study only one group. But in reality, race, culture, and gender all play a role in how we respond to medications. The study of individual differences in medicine is a relatively recent development.

A special issue of the journal Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics discussed “pharmacoethnicity,” which is how ethnicity affects how drugs are processed by the body. Even within ethnicities, people process drugs differently. For example, genetic allele necessary to process antidepressants was less prevalent in Ethiopian (9%), Tanzanian (17%), and Zimbabwean (34%) populations than other African populations.

Just as we might be nearing a future of personalized medicine, maybe we need to think of our training and diet in a more personalized manner, too. A personalized training plan would play up to our unique strengths and address our individual weaknesses.

The Average Is Not So Average

Throughout my education, I wondered about individual differences. I saw treatments work well for some individuals but not so well for others. I did a postdoctoral degree on the topic and worked to create specialized statistical tools to measure individual differences.

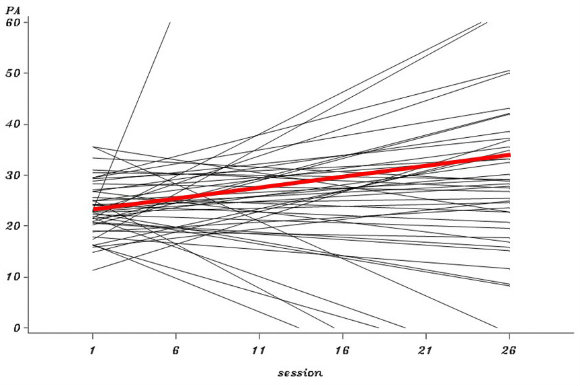

Below is a graph of an intervention study. In this figure, the red line represents the average. We can see that it goes up over time.

These results were published based on the assessment that it was a treatment that works (for the average person). But that red “average” line was actually calculated from many individual lines (in black). For some people, the treatment was a resounding success, indicated in the way their scores skyrocketed up. For others, the treatment had detrimental effects.

Imagine this treatment was instead a training program for elite athletes. Some people following this program would benefit greatly, most would benefit a bit, and some would get weaker from following this protocol. So how do you know if a program is for you?

Your Training Should Not Be the Same As An Elite Athlete’s

In working with CrossFit athletes, I have found many people wanting to emulate Rich Froning or Dmitry Klokov’s training. Both are known for high training volume with heavy weights. The problem is that most of us are not in the same place as Froning or Klokov. Their training background and years of experience prepared them for their current work.

We look up to elite athletes (Quadrant 4 athletes in Dan John’s and Pavel’s Easy Strength) and we may be drawn to emulate their training. But most elite athletes built a strong foundation of skills at younger ages. According to Tracking Football, 88.5% of the 2016 NFL draftees participated in a sport other than football during their high school career. Building a base of strength and conditioning allowed them to be successful in their specialization.

Given all that, to get to the level of Froning, Klokov, or an NFL draftee, you might be better off following one of their earlier training regimens as opposed to their current one. In short: unless you are already elite, don’t train like elites.

General Physical Preparedness Is Good Enough for Most

To determine the perfect individualized program for yourself, a great deal of work and experimentation needs to be done. With much less trouble, you can get close to the same benefits by following a program that works well for most people.

Simple & Sinister was written to assist most everyone in the general population. It blends strength, conditioning, and mobility work that will benefit everyone from Navy SEALs to older individuals. It is the program I would give to both my mom and someone training to prepare for the SFG Level I Certification.

Think S&S isn’t for you? Eric Frohardt, retired Navy SEAL and CEO of StrongFirst, chooses Simple & Sinister as his program to maintain strength and endurance throughout the year.

Become a Student of Strength

To individualize your strength and training program, you must first become a student of strength. As Pavel has said, to get good at programming, one must study programming. Just as a researcher does a literature review to find out what is already known, you must do the same in learning about strength, conditioning, and mobility programs.

Here are some great foundational articles to review:

Strength Programming

- The Origins of StrongFirst Programming: The Soviet System

- Patience of Strength

- Plan Strong for the Olympic Weightlifting Athlete

Endurance Programming

Mobility Training

- Miseducation of Stretching

- Revisiting Athletic Body in Balance

- A Long Way to Press

- A Speed Bump in the Get-Up

- Taking Charge of Your Back Pain

Be a Scientist of Strength

It is not enough to know about strength and conditioning, you must also act as a scientist and test everything. The Soviet scientists were known to be meticulous keepers of training logs and programs. They would pour over research logs to find what worked and what didn’t. To find the best individualized program, you must do the same.

Here are some tips to follow in your testing:

- Keep meticulous records. Record all possible outcomes, such as strength, perceived rate of exertion, diet, and mood. As a researcher, I don’t like subjective recording such as perceived rate of exertion. It is too difficult to compare across athletes. However, in your own record keeping, you will know what an easy lift feels like compared to a more difficult lift.

- Change only one variable at a time. When people attempt to make changes in their behaviors, they often make many changes simultaneously. But with simultaneous changes, we have no way of knowing which worked and which didn’t. The Whole 30 is unique in that it is a nutrition protocol that requires a strict diet for thirty days, followed by experimentation. The thirty days is to clean out the body from the previous effects of your diet. The experimentation phase then allows you to test to see how individual foods affect your body when they are reintroduced. This type of experimentation allows you to see what works one variable at a time.

- Stick to the program long enough. As a student of strength, you will be tempted to try on program after program. Each new program you learn about will seem to hold the “secrets” of strength for you. Be patient, finish your current program, and figure out what worked and what didn’t before you make changes.

Summary

As a researcher in individual differences, I suspect there is a perfect training program for you today and a different perfect training program for you next year. To find that perfect program, you have to be both a student and scientist of strength. You must put in a great deal of effort to learn and to test out programs.

But for most people, it would be best—and simpler—to follow a general physical preparedness program. Simple & Sinister is one of the best because we already know from the test of time that it works for the majority of people.

We are our own walking, talking, breathing science experiments. As the body changes over time so do our needs for variations in how we train & what we need to fuel our bodies. Thanks for reinforcing the need to journal for both diet & training purposes, for focusing on what our goals are depending upon what our current level of fitness might be. Keeping goals & expectations realistic is extremely important when working with the every-day athlete vs the elite athlete, and many trainers need to have this as a reminder!

Sold. You make an excellent case. One for the teachers and students of strength alike. Great piece!

Yes, be a scientist of strength! Thank you Craig for providing clarity to your process and I look forward to sharing the article.

Super helpful for some people I train for they, thus I, struggle with wanting to emulate those “elite athletes”. I will be sharing; thank you.

I would like to offer some…food for thought on your opening comments about “race” playing a role in how we as humans respond to stimuli. Without going into a detailed explanation -whole books have been written about the lack of genetic differences between the so-called “races”- there is no such thing as “race” where the separation of peoples is concerned. Thus, our schools, news outlets, justice systems, social media etc etc needs to end its use as a descriptor of peoples. Again without going into depth here, your second paragraph illustrates this lack of genetic difference as Ethiopians, Tanzanians, etc are all classified as belonging to the ‘black race’ in our society yet they clearly have wide ranging genetic differences. Thanks for “listening” and considering this food for thought. 😉

“I suspect there is a perfect training program for you today and a different perfect training program for you next year”

One of the best and most accurate statements ever published here, and applicable across many other aspects of life. Few on the associated forum understand it, but we should all take heed to it.

Great stuff, Craig.