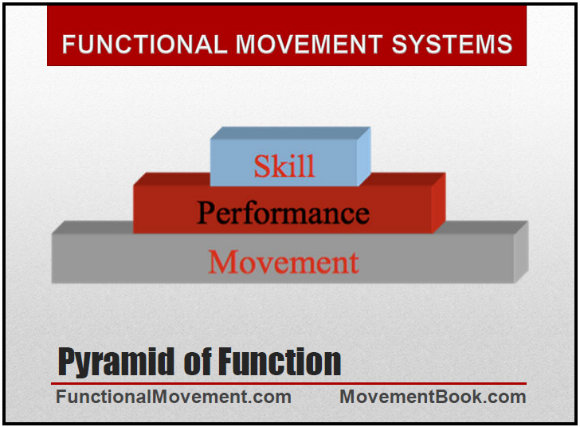

As SFGs and kettlebell practitioners, we understand and practice the principle that movement exists in a hierarchy. In fact, we have a hierarchy when it comes to teaching the kettlebell ballistics. Here is a simplified version we can use to illustrate the point:

- Hinge Drills (dowel, naked swings, butt to wall, etc.)

- Two-handed Deadlift

- Two-handed Swings

- One-handed Swings (and potentially one handed everything else above)

- Single Kettlebell Clean

- Single Kettlebell Press

- Single Kettlebell Snatch

To own the snatch, you must own the swing. To own the swing, you must own the deadlift. This is why sometimes in order to fix a kettlebell snatch, we look at a student’s deadlift. We should never allow a student to progress to an exercise for which they don’t own the foundational prerequisite.

The unloaded hinge shows us the student can recognize the pattern and have the mobility to perform it. The deadlift loads the pattern and shows us the student can stabilize the spine and use the hips as the prime mover to execute the lift. We know the swing is essentially a high-speed deadlift where the load projects forward and there is a rapid absorption of high loads at the bottom of the swing. The snatch takes all of the dynamics of the swing, multiplies them and then adds an overhead lockout (which brings issues of its own).

If the student cannot perform the hinge and deadlift, what chance do they have at stabilizing the ballistic swing or snatch?

In StrongFirst we often joke that we’re not “StrongOnly,” and many SFGs believe our unofficial name should be “SafetyFirst.” We never allow students to progress to a movement beyond their ability to safely execute it. We never deliberately put a student into a position in which his or she is not safe.

In all the StrongFirst manuals (Girya 1 and Girya 2, Bodyweight, and Lifter) there is an emphasis on safe execution and performance of exercises to a particular standard. There is even a toolbox of exercises, stretches, and other “voodoo” to fault find and fix problems. But these Certifications are to teach the principles of strength to a specific tool/application. Sometimes fixing a problem requires a diagnostic tool that can identify the problem area(s) more specifically.

Enter the Functional Movement Screen.

Functional Movement Systems

The Functional Movement Screen is the brain child of Gray Cook and Lee Burton. It is a collection of seven movement screens (plus three clearance tests) used to define movement competency and highlight potential movement problems—therefore, enhancing performance while reducing risk of injury. The FMS scores each of the seven screens from 0 to 3. Scores of 0 (pain) and 1 (inability to perform the movement), along with asymmetries, indicate some form of attention is required.

The screen and its corrective algorithm can be used to identify exercises and activities that are potentially harmful to a student, suggest alternatives, and provide a path to improving movement competency. Functional Movement Systems has as its core the understanding that all movement exists in a hierarchy built upon the developmental sequence. This is a complicated way of saying, “You have to walk before you can run.”

The philosophies of StrongFirst and Functional Movement Systems are incredibly similar, if not identical. This is hardly surprising considering that one of the FMS original team members was a young man by the name of Brett Jones, who went on to become StrongFirst’s Chief Kettlebell Instructor and Director of Education. Brett, and many others in the StrongFirst team, have been using and teaching the FMS alongside kettlebell training for over a decade and have found the two complement each other incredibly well.

Where FMS1 is a course that teaches how to apply and score the screen, FMS2 is the course that teaches what to do with that score. This allows for large teams/gyms to have many FMS1 certified trainers who can perform screens, then refer out issues (any zeros, ones, or asymmetries) to their FMS2 certified trainers who will then decide upon a course of action.

The purpose behind the FMS is most easily shown through a few situations I have seen repeated several times over in my career as a coach and trainer.

Situation 1: The Asymmetrical Runner

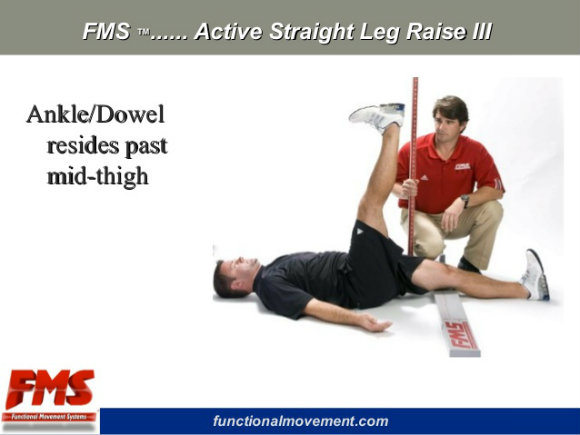

Sometimes distance runners (including OCR athletes, 10K runners, and triathletes) will display a 2/1 on the active straight leg raise (ASLR) screen. With this score, running is contraindicated.

In the FMS, a score of 1 means “you cannot perform the movement.” In this case, the movement is a leg scissoring pattern. If the pattern is asymmetric, as the 2/1 score indicates, then, to take a driving analogy, the tires on one side of your car are too soft. This means you get more wear on one side and get poor fuel efficiency. This analogy can directly carry over to people—one side is getting beaten up and you are not as energy efficient as you should be (which is a big deal for a distance runner).

By spending one to two weeks on corrective strategies, while avoiding running and performing other prescribed exercises, the majority of my students who originally scores 3/1 subsequently re-screened as 2/2 and returned to running. The majority also admitted the pain and discomfort they previously had (which they did not disclose on intake) was no longer present, and this lead to improved times on the field as they no longer fatigued as quickly.

I should add a quick note here that any pain experienced during a movement or uncovered during a screen should be referred out to a physiotherapist or other medical professional. The screen does not deal with pain. Pain and its treatment is the realm of suitably qualified medical professionals.

The ASLR, among other screens, is also an indicator for whether an individual is ready to perform deadlifts, swings, cleans, and snatches. It is entirely likely that the person who scores poorly on the ASLR has a mobility, stability, or motor control issue that will impact his or her ability to safely execute these movements.

This is a red flag all kettlebell instructors should be aware of, as these movements are our fundamental bread-and-butter techniques. No amount of verbal cuing is going to change this. Sometimes you need to get under the hood and address the underlying problem, which is what the screen and corrective algorithm allow us to do.

For those who teach in groups (small, medium, or large) the screen allows us to make sub-groups (or teams) within the overall group. This allows us to tailor the group session by having each team break out from the main group to perform their corrective exercises together. It also allows us to scale a workout for each of the specific teams. For example, members of a team who have only recently reclaimed their ASLR score of 2/2 may want to spend a few training sessions practicing the slow strength of their deadlifts before moving on to their swings and cleans.

Situation 2: The Overhead Presser

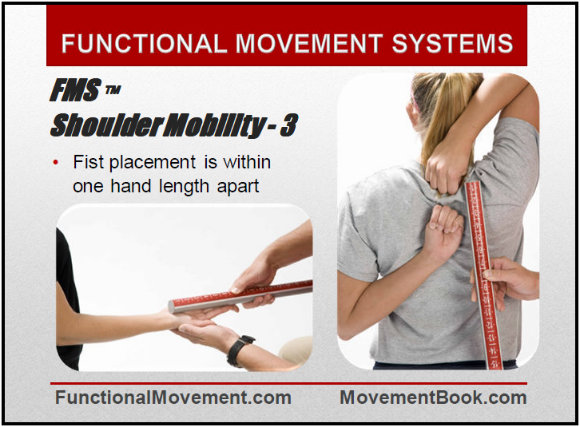

Many recreational athletes who hold down nine-to-five day jobs riding a desk can show a poor score on the shoulder mobility screen, be it a 1/1 or a 2/1. This screen, among other things, looks at a combination of shoulder mobility and thoracic spine (t-spine) extension. In these athletes, sitting down all day can wreak havoc on their t-spine, removing a lot of the ability for the t-spine to extend.

Part of a successful overhead lift is the ability to stack the center of the weight being lifted in a straight line directly over the shoulder, hip, and mid-foot, with a neutral spine supported by a braced core. If the t-spine cannot extend as far as it should, this can result in one of two problems:

- The athlete becomes prematurely fatigued, as he or she is essentially doing a press into a front raise position and the small anterior deltoid muscle becomes fatigued before the big prime movers in the press.

- The athlete allows the lumbar spine to extend as the thoracic spine cannot do its job, and this can lead to the development of low back pain.

A poor or asymmetric score in the SM screen means that any overhead work is contraindicated, but by addressing this issue, we can potentially fix the two problems above. As a result, we either increase the strength of our students by making their technique more efficient or remove pain and discomfort from their life (which is always welcome).

Situation 3: Swings Hurt My Back

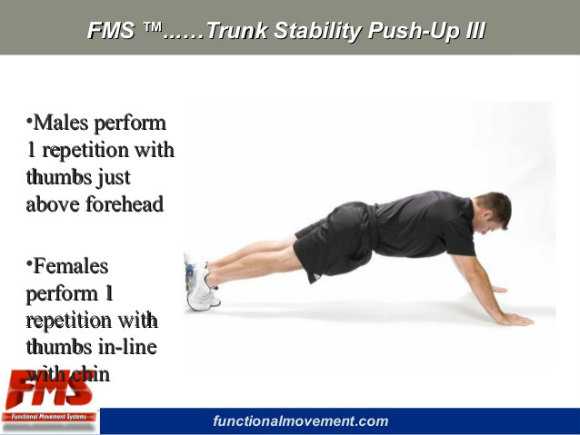

We hear this often from students and athletes who haven’t been correctly coached in the lift. The two screens that reflect greatest on any hinging movement are the ASLR (covered above in our running example) and the trunk stability push-up (TSPU).

A score of 1 on the TSPU can be an indication of a lack of awareness of how to brace the core, which is a skill required for any movement that transfers force from one limb to another (so it’s very important). A student who scores a 1 on the TSPU may not be able to brace against the weight of his or her own body and will run into issues with a high-speed loaded hinge. This is the reason that a score of 1 here means swings (and deadlifts) are contraindicated.

Being able to brace the core isn’t just about heavy lifts though, it is also about force transfer from the ground to the working hand or foot. To create force for throwing, kicking, running, jumping, or punching, the student normally pushes against the ground with the leg(s), and this force is transferred to the working limb (the one doing the kick, throw, etc) through the core musculature. A core that cannot transfer force efficiently means that an athlete either falls short of her full power potential or, in the case of more endurance-based activities, she will fatigue much earlier than perhaps she should.

The FMS Principles + StrongFirst Principles

Functional Movement Systems employs three core principles, and all three are demonstrated in the above scenarios:

- First, move well. Then, move often. (Natural Principle)

- Protect, correct, and develop. (Ethical Principle)

- Create systems that enforce your philosophy. (Practical Principle)

By understanding the Natural Principle, we acknowledge that the movement hierarchy exists and must be worked through progressively. The Ethical Principle allows us a method to protect the students from damaging themselves and provides a path to improve movement and performance. The Practical Principle means knowing your craft and knowing how to apply it consistently and repeatedly for all to benefit from.

StrongFirst is a School of Strength, schools (should) teach systems and methodologies that remove any guess work. We often joke that 90% of questions at a StrongFirst Certification can be answered by, “What does your manual say?” The Functional Movement Systems approach is also very systematic (the name should be a giveaway) and has an entry point (the screen) that can then lead to other screens and capacity tests:

- Breathing Screen

- Y-Balance Test

- Motor Control Test

- Fundamental Capacity Screen

- Selective Functional Movement Assessment (SFMA, the clinical model if pain is present)

All of these feed into the FMS corrective algorithm.

SF + FMS = Framework for Success

There is a reason that more and more StrongFirst instructors are learning and applying the FMS principles and methodologies, and vice versa. The FMS allows us to use a laser focus to find the weakest links and create programs that bring huge gains with minimum time and effort. The FMS also gives us a framework that bridges the gap for students returning to movement from years of a sedentary life or returning to sport after injury (when discharged by their medical team).

In short, the FMS allows us to protect our students from things that can harm them and gives us a plan to get them moving toward their potential. Where StrongFirst principles fit in is that our teaching progressions for movement honor the same principles as the FMS (you can’t skip a step), as do our programming strategies for strength and endurance.

We know in StrongFirst that our principles are the quickest and safest way to improve physical performance. When we add in FMS, we are further turbo-charging and enhancing our practice.

In my opinion, besides certification from your national governing body, FMS II and SFG are the primary certs that every trainer, S&C coach, and rehab professional should have under their belt. Hoping to get my SFG to complete it soon!